Hear and now: Sounding boards offer willing ears and guiding hands

Sounding boards are important listeners who can deliver crucial feedback, perspective and story guidance. But they also can provide invaluable support as your career unfolds.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

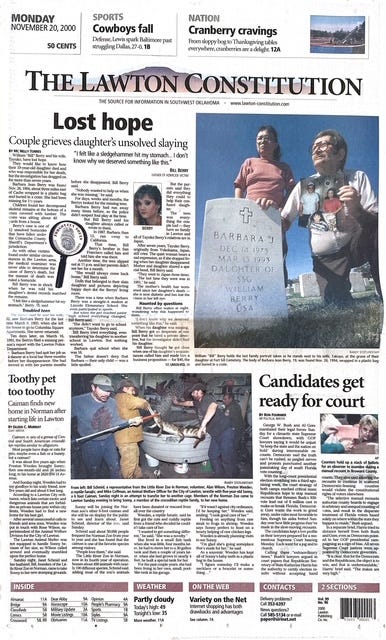

It was June 2000 and I was writing about another naked woman’s body found at an isolated area in Comanche County’s outskirts.

Mandy Ann Raite was 21 when police found her decomposing corpse June 17, 2000, at a small creek off a dirt road less than a mile west of Bethel Road on East Cache Road. She left a young daughter behind.

Raite was among 11 homicides under Comanche County Sheriff Department’s jurisdiction that had remained unsolved from 1990 to 2000.

Since I began covering the criminal justice beat, I’d heard the stories about the problems contributing to the sheriff’s abysmal homicide solvability rate. Local and state investigators told me — off the record — disturbing stories about the sheriff’s untrained personnel contaminating crime scenes and compromising homicide case evidence.

I was at a crossroads because I knew the managing editor was not going to approve such a project and give me the time I needed to dig into these deaths. I needed a sounding board to provide advice, perspective, support and guidance. It would be my first investigative series.

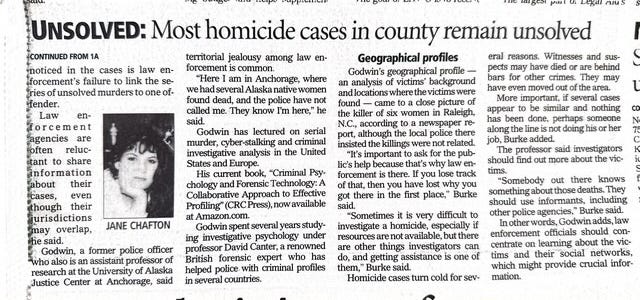

I was lucky that my first unofficial sounding board was on an Investigative Reporters and Editors’ member email list. The group is a community of like-minded investigators who gave me thoughtful advice, guidance and good sources, such as criminal investigative experts.

The initial encouragement to begin working on these stories came from local and state law enforcement perhaps because the sheriff never requested their support and help.

But as a young reporter covering a hectic beat, I knew my shortcomings. I had no experience producing investigations and needed some smart direction to get started.

First, I read. Pulitzer Prize winner and former Miami Herald crime reporter Edna Buchanan described how she approached investigations in her nonfiction books “The Corpse had a Familiar Face” and "Never Let Them See You Cry.”

As she advised, I said nothing to my newsroom bosses until I accumulated a body of documents and reporting after months of work on my own time, off the clock.

I spent those months reviewing police records, reading autopsy reports and interviewing experts, law enforcement officials and the victims’ families and friends. I tried to get any piece of information that would help me piece together the story behind each woman’s death.

My strategy was to have 70% to 80% of the work before I pitched this project with the caveat that I needed time to complete it. Initially, I didn’t know what I had and how many stories my reporting could produce.

My silence proved savvy. I’d eventually learn that you don’t want to get editors excited with a half-baked idea and then come out empty-handed.

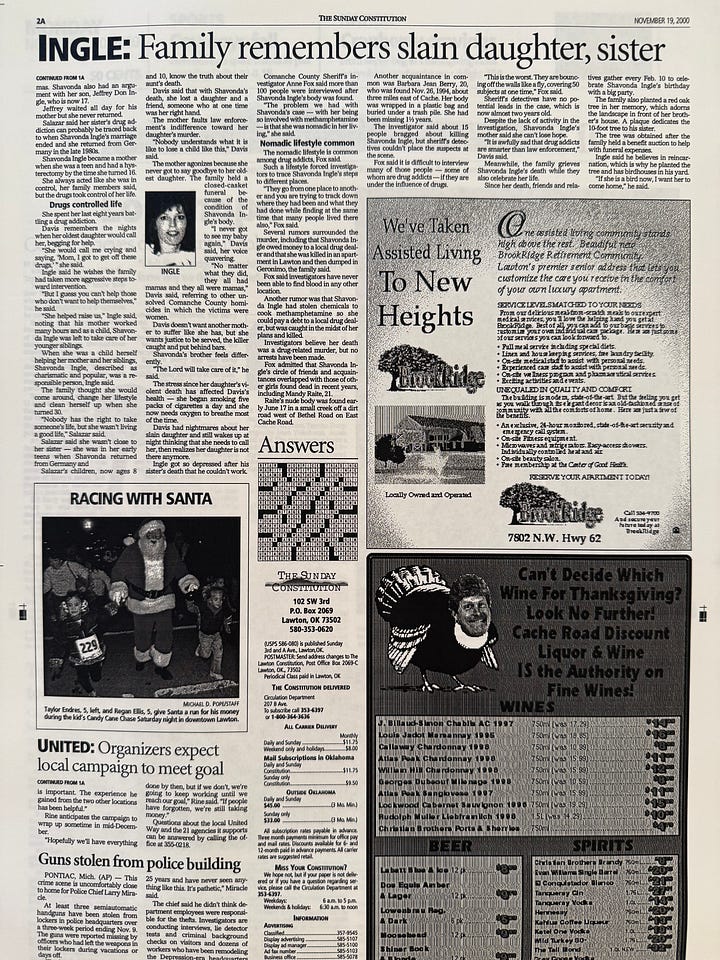

As I began to connect the puzzle pieces, a theme emerged that became my nut graf. Several victims had things in common — they were found in remote areas and were often involved in the underworld of drugs, prostitution. Some of them knew one another.

The sounding board in my newsroom, composed of several experienced reporters whom I trusted, helped me build an outline and map out the number of stories I could do.

I led the series with Mandy Raite because she was the last woman found. It was heartbreaking to watch her young daughter, who was then 2, holding and kissing her mother’s picture as I interviewed her grandmother at their home.

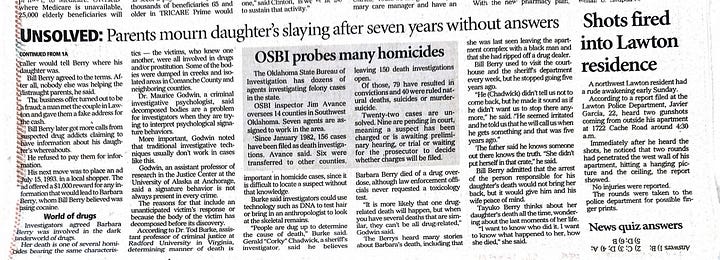

My investigation led to a three-part series, “Forgotten Souls,” a title I chose because my reporting showed law enforcement had done little or nothing to investigate these cases.

Dr. Maurice Godwin, a criminal investigative psychologist my IRE sounding board pointed me to, told me in interviews law enforcement view people with substance abuse struggles and sex workers as disposable people.

“There’s a perception that they are less than death and outcast from society,” he told me. “There’s no doubt about it. If these were college girls, there would be more investigative efforts.”

Journalists have documented this type of attitude over the years and documentarians have done the same. Netflix’s docuseries, “Gone Girls,” about the Long Island serial killer, is an example of how this indifference becomes a huge impediment because investigators are not focused enough to see trends and threads that link cases and leads that could potentially shed light on a suspect.

The Long Island serial killer case traces back to 2010, when investigators started finding women’s bodies on Gilgo Beach on Long Island’s shore. The Netflix series has helped put the case back in the headlines.

Law enforcement agencies’ internal impediments — including unqualified people overseeing cases, crime scene contamination and jurisdictional struggles all contribute to homicides cases going cold while killers continue to hunt victims, as happened in the Long Island case.

But sometimes, internal biases and personal conflicts also hinder police investigations.

Effective sounding boards

One of the biggest lessons I learned during my first investigation was how valuable sounding boards can be. The people I approached gave me invaluable feedback, such as which documents to request from government sources, and let me bounce ideas off them. They also helped me refine my approach and avoid pitfalls as I worked around a sheriff’s department that was unwilling to cooperate with my reporting.

Over my career, I found sounding boards that collectively helped me with different objectives. I created my own sounding board network in newsrooms to give me perspective on story ideas or help me troubleshoot challenges as I worked on investigative stories. Sometimes, I would use these sounding boards to revise a rough draft; they helped me strengthen the writing and build stronger narratives.

I have used the same approach to developing sounding boards that I have used to build diverse sources, a topic I discussed recently. I spent time building relationships and cultivating rapport, and the work has paid off. Over my career, sounding boards have given me career advice, feedback and thoughtful reviews of my job applications.

Years ago, as I began to build and seek funding to launch Florida Center for Investigative Reporting, I sought a sounding board with experience in nonprofits. I needed help understanding the requirements to obtain the 501(c)3 approval from the IRS.

Before I accepted the job offer as an editor at the Center for Public Integrity in late 2020, I reached out to my sounding board as I tried to gauge whether this position was the right fit for me.

And as I applied for jobs last year, one of my sounding board members gave me a reality check — she told me my cover letter, as written, was too modest and left out important accomplishments. Cover letters, she said, were a place to show achievements proudly and shine like a star.

“How can you leave out that you were the 2022 recipient of the Gwen Ifill Award?” she wrote to me via text messaging. “You received that because of your career-long dedication building diversity, equity and inclusion in the news media.”

“You got that award because you are a badass,” she wrote.

Sounding boards can also support you emotionally when you face challenging situations at work.

I talked with my sounding boards when I was managing difficult people and facing sensitive situations. These discussions helped me to think rather than overreact to something and to collect a variety of perspectives before I made big decisions.

A sounding board helps you stay focused and motivated as you build relationships with people you admire, value, respect and see as mentors.

As billionaire investor Warren Buffett once said, “Surround yourself with great people.”

That’s the makeup of a sounding board.

The courage to ask for help

Sometimes law enforcement create joint task forces to investigate organized crimes such as drug and human trafficking. But I wonder whether in small rural communities such as Comanche County, a sounding board could help elected officials, such as sheriffs, solve crimes.

I’m certain the sheriff could have benefited from help from experts in crime scene evidence collection, homicide investigations, data analysis and serial killer profilers when he was investigating the deaths of the women who were dumped naked in isolated areas.

Comanche County, the home to a military base (Fort Sill) and a connecting highway Interstate 44, running northeast to Oklahoma City and south to Wichita Falls in Texas, is a rural region with a transient population, posing another challenge for investigators.

Traditional investigative methods such as interviewing people and autopsy reports, as experts told me then, are not enough to investigate these types of crimes, especially if a suspect is connected to more than one homicide.

Another problem was the inability to collect more forensic evidence because the bodies were decomposed. The state medical examiner ruled in Mandy Raite's death accidental even though the circumstances suggested that someone dumped her naked body in a seemingly unfindable place.

Dr. Maurice Godwin, the criminal investigative psychologist, told me that a body’s decomposition poses a big problem for investigators because “it destroys all the forensic clues and any time of psychological signature behaviors.”

“There might be a specific type of thing the offender might be doing to the victim but it’s hard to detect that when a body is decomposed,” Godwin told me. “Two weeks after it was murdered or later is bad and if the chest is badly decomposed, that’s a problem … too.”

Godwin is still known today for integrating demographics, environmental psychology, landscape analysis, crime site information and other pieces of information to create a profile of abductors and serial killers. Godwin has written books and is an adjunct professor at Campbell University in North Carolina.

Investigating these cases requires patience, consistency, focus and the willingness to use new approaches and technology. But law enforcement agencies that lack resources or expertise may sometimes need to seek help from the public and other investigators.

“It is not a bad reflection to ask for help. It’s asking for assistance when assistance is needed. Law enforcement needs to understand that it is OK to ask for help,” said Dr. Tod Burke, who was an assistant professor of criminal justice at Radford University in Virginia and a former police officer.

Over a year after I left Lawton and moved to South Carolina, another woman was found dead near where Mandy Raite’s body was dumped.

This time, the FBI came in and said publicly that it believed this was a serial killer’s doing.

I wished I had been there. I would have told the sheriff that he had a problem. He had a serial killer in his backyard and direly needed a sounding board.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.