A jailbreak, a scoop and the fight for equal pay

The biggest jailbreak in Comanche County’s history helped a young reporter shed light on the basic idea that women should be paid the same as men for doing the same work in the newsroom.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate the journalism’s chaotic, toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a long-time investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

My personal cellphone rang after 2:45 a.m. on March 11, 1999.

When I answered, a female source who worked inside Comanche County Jail began to speak in Spanish. She had a scoop for me, she said, sounding anxious — a jailbreak had taken place just moments before she dialed my number.

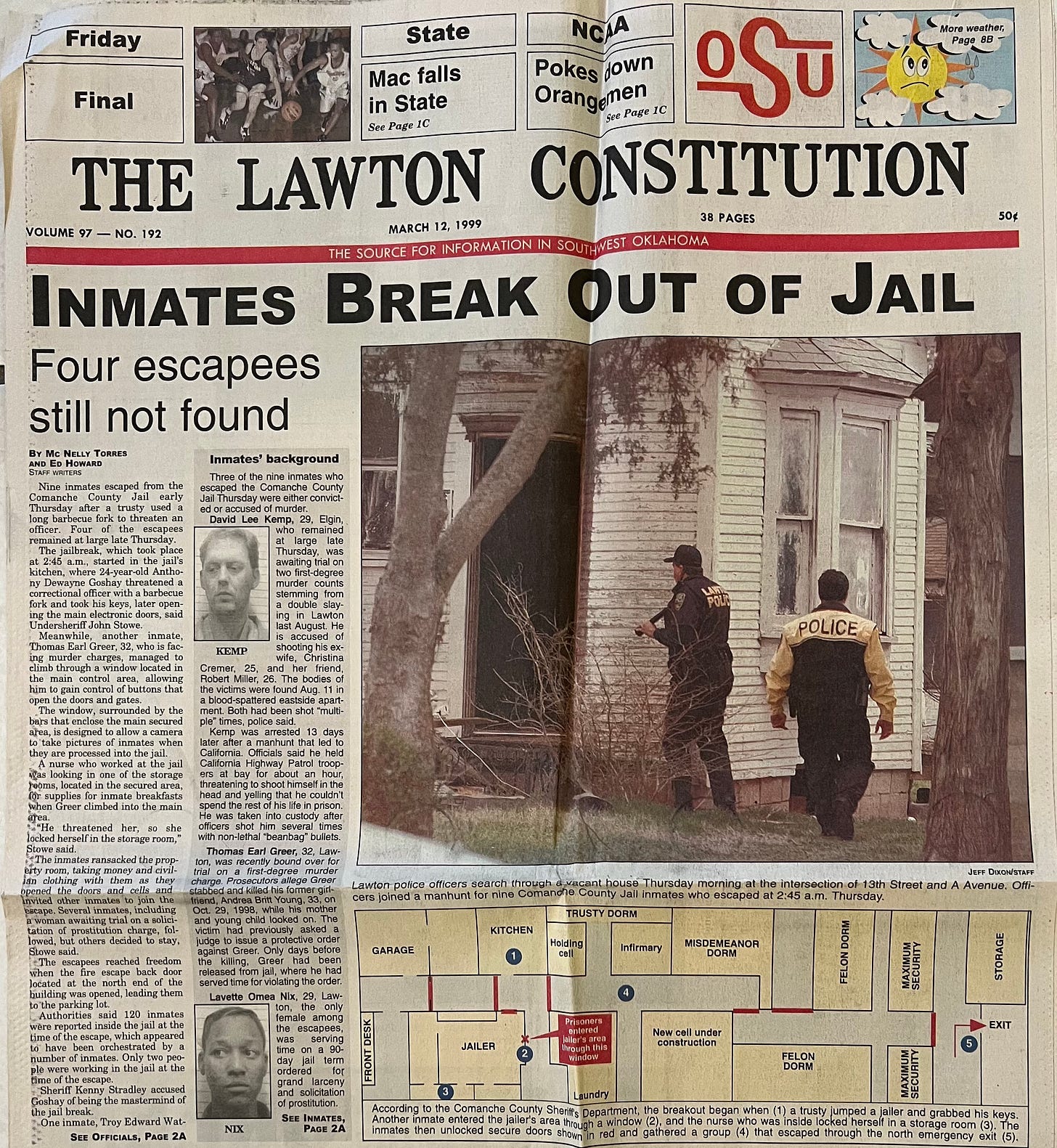

Nine inmates had walked out of the county jail located at the lower level of Comanche County Courthouse in downtown Lawton after an inmate threatened a correctional officer with a long barbecue fork.

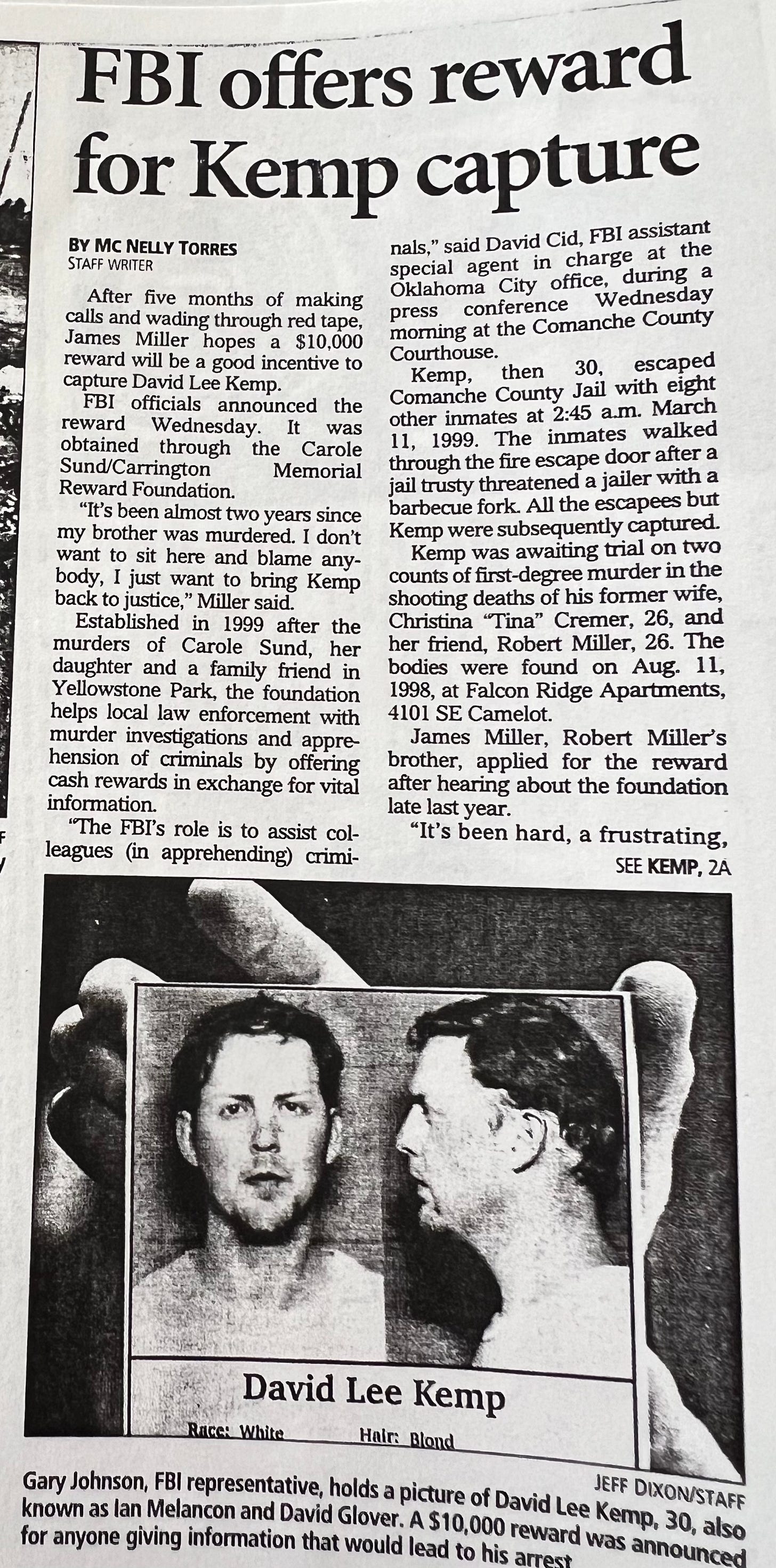

Among those at-large were three men charged with murder, including David Lee Kemp, then 29, who was accused of killing his ex-wife and her boyfriend.

“Hurry up and come here now!” my source screamed. “You need to be here!”

This had been a contentious time for me at The Lawton Constitution. Days before the escape I had a tense meeting with the managing editor in his office about my salary after I discovered a gender pay gap between my peer and me.

Tom, a white guy from Texas, and I shared the criminal justice beat and we had about the same experience. Tom shared details about his salary over drinks before he left town for a new gig in Oklahoma City.

I was shocked initially, anger and disappointment followed.

When I confronted the managing editor, he was furious and tried to deny it. Then I shared my source.

His face turned red. “I would have fired him if he was still here,” he said.

I thought a lot about this moment in my career over the years and how he brought up his grandfather’s affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan when the conversation turned contentious like a non sequitur in a story that needed to be taken out. He curiously used a heavy southern accent when he talked about his grandpa and a big smile usually followed as he recounted how he always noticed his grandfather’s white klan hood inside the barn during his summer visits to Mississippi as a kid.

I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. There’s no KKK there and while I know the violent history against Black and Indigenous people in this country, I was ignorant, at the time, about how these microaggressions and racial undertones were used.

With time and as I continued to move throughout my career, I learned by first experience how words are used as a weapon to disempower people of color.

But I ignored the comments. His tactic didn’t have the intimidating effect he was going after.

And that made him angrier.

“If you have any complaints about your compensation, you are welcome to go downstairs to HR.”

“No, I’m not going to HR,” I responded. “I’m going to file a complaint with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) because this is a clear case of gender and race discrimination. I also had a witness and documents.”

That’s when he ended the meeting saying that he could no longer talk to me about “personnel matters.”

Days later, the largest escape in the history of Lawton was about to terrify this small community for weeks and months and I was the first reporter to learn about it while the whole town was asleep.

The power of words

During the call, I wrote down the details the female jailer shared with me about the jailbreak. I continued to scribble details and questions into my notepad after the call ended.

I sat in my bed for a brief moment, thinking about what to do next.

That morning, I wielded the power. It was time to dial his landline number and wake him up. This was a big story and adrenaline rushed through my veins.

In most scenarios, including in the news business, a call that late or that early in the morning never bears good news.

After I briefed him about the escape, he cleared me to do the reporting needed to cover the story.

“Keep track of those hours,” he said, noting that I would be compensated for overtime.

He knew I had multiple sources in all the agencies on my beat: police and sheriff departments, county clerk’s office, district attorney, county jail, juvenile agency, 911 dispatchers and the Wackenhut prison. I had good relationships with the judges, their court reporters and bailiffs.

I made a couple of calls to sources in the police department, where most officers, including detectives, had a deep dislike for the sheriff.

It was going to be a long, long day. I was ready for it.

The sheriff and the press

Comanche County Sheriff Department and the sheriff, an elected official, oversaw the county jail.

In those days, the only journalism game in town was the TV station and The Lawton Constitution. The competition was fierce.

But, like many small outlets competing with television news, The Lawton Constitution was at a disadvantage. The sheriff — a shrew politician — loved TV reporters. They gave him what he wanted — a way to talk directly to the public without any fact-checking. The reporters took what he said and ran with that.

I didn’t. I knew the sheriff department wasn’t known for efficiency, good investigators or transparency.

So, I asked the questions he didn’t want to answer. I wanted documents pertaining to the county jail, such as health inspections, which he often refused to provide violating open records laws. And my stories always contained details and context from several sources aside from him. But this was big news and the sheriff had a lot explaining to do.

How could inmates possibly get ahold of a barbecue fork to threaten a correctional officer?

How could nine inmates walk out of the jail so easily?

Where was the breakdown in protocol and security?

Who was at fault? What did we know?

Who is investigating? Had he asked an outside agency to conduct an internal review?

The sheriff had little to say when I walked into the sheriff’s office at the courthouse early that morning.

His deputies were conducting a search, he said. That’s it.

News about the escape was everywhere then, and a CNN team from Oklahoma City had arrived in town. But I had the advantage. I knew this town and these people and where to get what I needed.

I visited the clerk’s office, where all the information about the inmates were in files. I already had the names. Now I needed information to profile each escapee.

I headed back to the newsroom to write my story. I was confident that, if I needed anything, the clerk’s office would provide the information. That office was part of my daily rounds and I was allowed to pull out files in the backroom as if I were a worker there.

The newsroom was noisy as I walked in after 2 p.m. It was a big story and everybody was talking about it. All the editors were waiting for me to provide the latest update. Another reporter, Ed Howard, was assigned to work with me.

I sat behind my computer and began to write the story. I had started crafting a straightforward lede on my head while driving back from the courthouse.

“Nine inmates escaped from the Comanche County Jail early Thursday after a trusty used a long barbecue fork to threaten an officer. Four of the escapees remained at large late Thursday,” the lede read after edits from editors and the copy desk.

After that, I followed with details on how the incident unfolded in the kitchen where an undersheriff said, a 24-year-old inmate used the barbecue fork as a weapon, took a jailer’s keys and opened the electronic doors.

Be your best advocate

I called the clerk’s office to obtain more information about individual escapees that the copy desk needed to build individual profiles.

Then, I returned to my draft. The computer screen had my sole attention. Even in the noisiest newsroom, I can shut down any distraction or noise. Nothing matters if it doesn’t involve my keyboard, notes and my screen. I kept writing when I heard someone shouting my name.

“Torres! My office now!” the managing editor shouted as he stood in front of his office with a Diet Coke in one hand.

I walked in. He pointed to a chair in front of his desk and asked me to sit. I was anxious because I had been up since the call with the scoop.

He walked behind his desk and said: “I’m very impressed with how you got this scoop, the reporting with this story and the fact that you seem to have more information than the competition.”

“Thank you,” I said. “It’s been a long day. Anything else? I need to finish writing.”

“No, I’m not done,” he answered. “I want you to know that I approved a raise for you today, effective immediately.”

I didn’t know what to say. I was tired and eager to ready the story for the copy desk. But I said thank you.

Was there anything else to say? Maybe, but sometimes saying nothing is better than opening your mouth and saying something you’d regret.

Maybe he worried about what I was going to do next. Compensation discrimination and pay inequities build tension and distrust in any workplace including newsrooms.

I don’t know what he thought. But here’s what I know.

Within a matter of days, we had gone from him trying to intimate me with HR and appalling tales of the KKK to praising my worth. He’d done a 180.

I also know this: Long after the CNN crews left and most of the inmates were captured, I continued to cover a search that continued for years after I left Lawton. Kemp for 14 years became one of the most wanted fugitives in the U.S. He was featured several times on famous programs such as “America’s Most Wanted” and “Unsolved Mysteries.”

In 2013, a former colleague called me to give me some unexpected news — Kemp reappeared in Comanche County and turned himself in to the sheriff department. He refused to say how he managed to elude capture for over a decade.

He was tired of running, he said.

Sometimes it takes a simple conversation to get what you deserve. Sometimes it’s a confrontation. And sometimes, it’s doing your job so well that denying your worth is so absurd that it puts them in legal jeopardy.

You do what it takes to get what you deserve.

Unfortunately, I encountered more pay inequities as I moved onto other jobs. And I had to learn on my own how to negotiate and deal with each situation as I found out how underpaid I was compared with white colleagues.

But the lesson was simple: You are your best advocate.

Thanks for reading.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.