Taking credit when it isn’t due

A young reporter learns early in her career important lessons about plagiarism and dishonesty and how crucial it is to acknowledge someone's contribution to a final product.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

It was a humid afternoon when I got the assignment to join a photographer and chase tornadoes spotted outside of Lawton, Oklahoma.

This was not my cup of tea. I grew up in hurricane alley on Puerto Rico's southeast coast. But tornadoes are different from hurricanes.

Tornadoes are unpredictable — no one can guess the trajectory after a storm funnel touches the ground and destroys everything on its path.

It was May 4, 1999, the peak of Oklahoma’s tornado season and this one would be deadly.

We drove to the Duncan area but found no signs of tornadoes. It was cloudy and humid, but there was no rain or hail. We returned to The Lawton Constitution’s building and heard people in the newsroom talking about another tornado spotted near the military base, Fort Sill.

Soon I found myself following colleagues from editorial and advertising upstairs to the building’s roof, which had a view of the city and beyond north of us.

What I saw terrified me. There was a humongous storm heading north toward Oklahoma City and a tornado with a half-a-mile-wide funnel.

Everybody on the roof watched in awe.

I had seen funnels hanging from a cloud and weathered hurricanes in Puerto Rico as a child, but I had never seen a tornado that was both so big and so beautiful.

Though the tornado was miles away from us, the wind was starting to pick up; we could feel it on the building’s roof. Jeff Dixon, one of our senior photographers, documented everything with his camera.

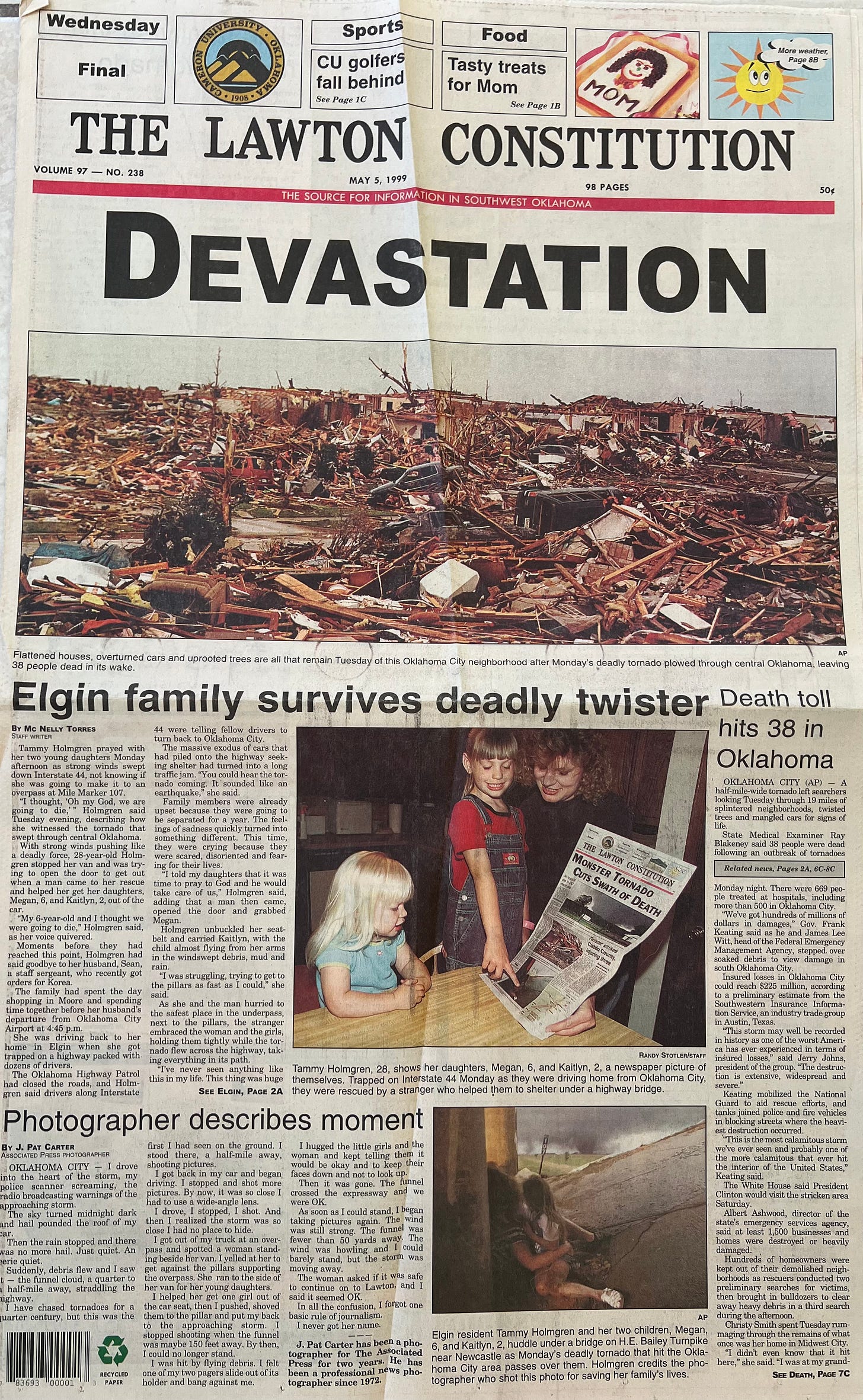

The F5 tornado, the highest category with wind speeds between 261 and 318 miles per hour, continued pushing north, wreaking havoc on everything on its path. It became the deadliest tornado in the state’s history, killing 36 people and causing $1 billion in damage.

The next day, the newspaper’s full staff was in the newsroom as we planned the aftermath coverage. One of our editors noticed a first-person story on The Associated Press wire about a photographer who helped a woman and her two children take refuge under a bridge as the tornado approached Oklahoma City.

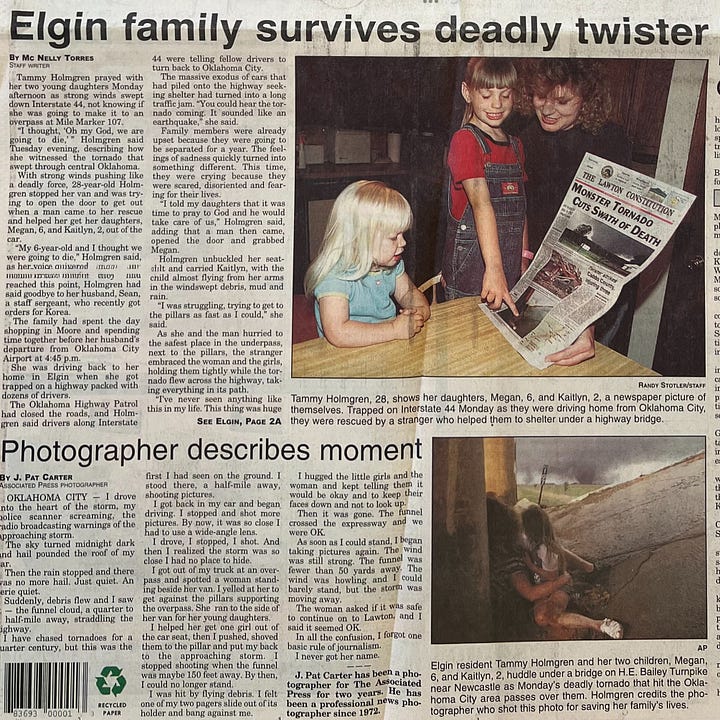

He spotted the woman, Tammy Holmgren, standing by her van on Interstate 44, afraid and confused. J. Pat Carter, an AP photographer, wrote a short first-person account about chasing the tornado, getting close to it on the highway and deciding he needed to find a place to shelter. As he kept driving, he spotted Holmgren near the underpass.

Carter helped Holmgren and her two young daughters take refuge under the bridge: he huddled them against the columns as the tornado roared north.

Though the winds were strong, he managed to get up when he thought it was safe to do so and take a famous picture of the storm that was published all over the world.

The picture was dramatic, but the last two sentences of his personal account got our attention.

“The woman asked if it was safe to continue on to Lawton and I said it seemed OK. In all the confusion, I forgot one basic rule of journalism. I never got her name.”

Word of mouth travels fast

I decided that getting this name was my mission that day. I thought it would be amazing to find this military wife and get her story. I called people all over the military base and my colleagues did the same.

We had no social media then, but word got around, and at some point during the day, she called the newspaper.

Hours later, a photographer and I were in the living room of her house in Elgin.

She told me she was at the Oklahoma City airport with her daughters, ages 6 and 2, shopping and spending time with her husband, who was leaving his family and heading to South Korea for a yearlong military assignment.

The mother and young daughters were sad as they traveled home. But sadness turned to terror as she realized that she had driven into a chaos and joined dozens of drivers trapped in the highway. The Oklahoma Highway Patrol was redirecting drivers after they closed the roads and drivers on I-44 were telling other drivers to turn back to Oklahoma City.

As all of this was happening, Holmgren could hear the tornado getting closer.

“It sounded like an earthquake,” she told me.

As Holmgren stood by her van, confused and terrified, a stranger hurried them to the safest place in the underpass, near the pillars. He embraced them tightly as the tornado flew across the highway.

Holmgren had no idea who this man was or what he did for a living. She never got his name.

After the tornado moved past them, the stranger, Carter, ensured that she and her children were safe. Then, he left.

“Here is my life flashing before my eyes and this guy is taking photographs,” she said. “Who would do something like that?”

The Lawton Constitution published Carter’s picture of the mammoth storm, which went out on the AP wire. It also published his first-person account under the story I wrote.

Holmgren had no idea she and her daughters were in that picture until a co-worker told her. She told me she was in awe of the tornado’s destruction as she drove to Elgin.

“I never expected to witness something like that,” she was quoted in the story. “There are no words to describe it.”

A proud moment stolen

I was so proud of myself and the newsroom because we’d identified Holmgren and I’d gotten her story so quickly. It was published May 5, 1999, on the paper’s front page, below the fold.

Carter’s first-person account was also published under my story.

As I entered the newsroom the next day, I sensed tension.

Someone at the AP had taken portions of my story after my editors sent it to be posted on the AP wire and had used the paragraphs verbatim for a story similar to what we had published. But the AP story didn’t have my byline, credit line or mention that The Lawton Constitution did the story first.

It was plagiarism — the worst kind you can imagine.

This AP writer decided that he would take credit for my, and my newsroom’s, work after he called Holmgren and asked a few questions.

I was furious. So were my colleagues. Our sports editor called the AP and complained.

The word got to the managing editor, who did … nothing.

I don’t remember the name of the AP reporter who decided that stealing my work was the assignment that day. But shortly afterward, the AP’s bureau chief stopped at our newsroom to take the managing editor to lunch.

As the bureau chief walked in, people in the newsroom complained to him about what had happened.

Then, the managing editor came out of his office and walked with his lunch guest toward my desk.

“This is Mc Nelly Torres, our crime reporter,” the managing editor said.

The AP bureau chief said, “You don’t look like a crime reporter.”

I stood up, looked the AP bureau chief in the eyes, shook his hand and said: “I didn’t know crime reporters needed to look a certain way.”

I was livid.

This guy had humiliated me in front of my colleagues with his offensive 1950s notion of how a crime reporter should look.

I spoke up because I knew the managing editor wouldn’t defend me.

The newsroom went quiet. Then, our managing editor and the AP bureau chief left for lunch.

All of my colleagues agreed that the comment was misplaced and disrespectful.

Two hours later, our managing editor stopped by my desk. I couldn’t resist telling him what I thought.

“So what did the bureau chief mean that I didn’t look like a crime reporter?’ I asked. Is that because I’m not a white guy?”

He dismissed my comment.

How dare I complain about the AP plagiarizing my work.

Unfortunately, this would not be the last time someone tried to take credit for my work or ideas.

That’s why giving credit to each person I work with on team projects works with me. If you contribute to the final product in any way, I’ll acknowledge you.

There are times in your career when you need to speak up and show people that you have value. There will be times you need to value other people, and humbly acknowledge their contributions.

It’s the right thing to do. Don’t miss your chance.

Note: I’m eternally grateful to my sounding board but also to those who have provided incredible feedback and edits to this newsletter.

Matthew Crowley: Your contributions as an editor of Don’t Forget My Voice are thoughtful and on point. I’m glad we met.

Luis Joel Méndez González: You might be young, but your wisdom and feedback speak volumes of who you are: a great human being. Thank you.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.

Thanks for sharing your experience. It's tragic that not only was your work stolen, but the injustice was minimized.