Scoops and tips are discovered here; learning to meet them in the moment

Most journalists are inquisitive by nature, but that requires them to be always alert and ready to ask questions.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

Tips and scoops come in different forms and from different sources. Someone whispers something in your ear, your curiosity leads you to documents or data solidifies a hypothesis to uncover an issue.

As journalists, we learn how to sort snippets of information — which ones have immediate story potential and which to stash for later, when there’s time to pursue them.

But sometimes, tips arrive like lightning bolts, maybe during public meetings.

That’s what happened one fall morning in October 2000. A colleague covering the Comanche County Excise Board came to the newsroom with a tip — a letter the chairman of the board shared with board members during a public meeting. He’d expressed concern about the letter’s content.

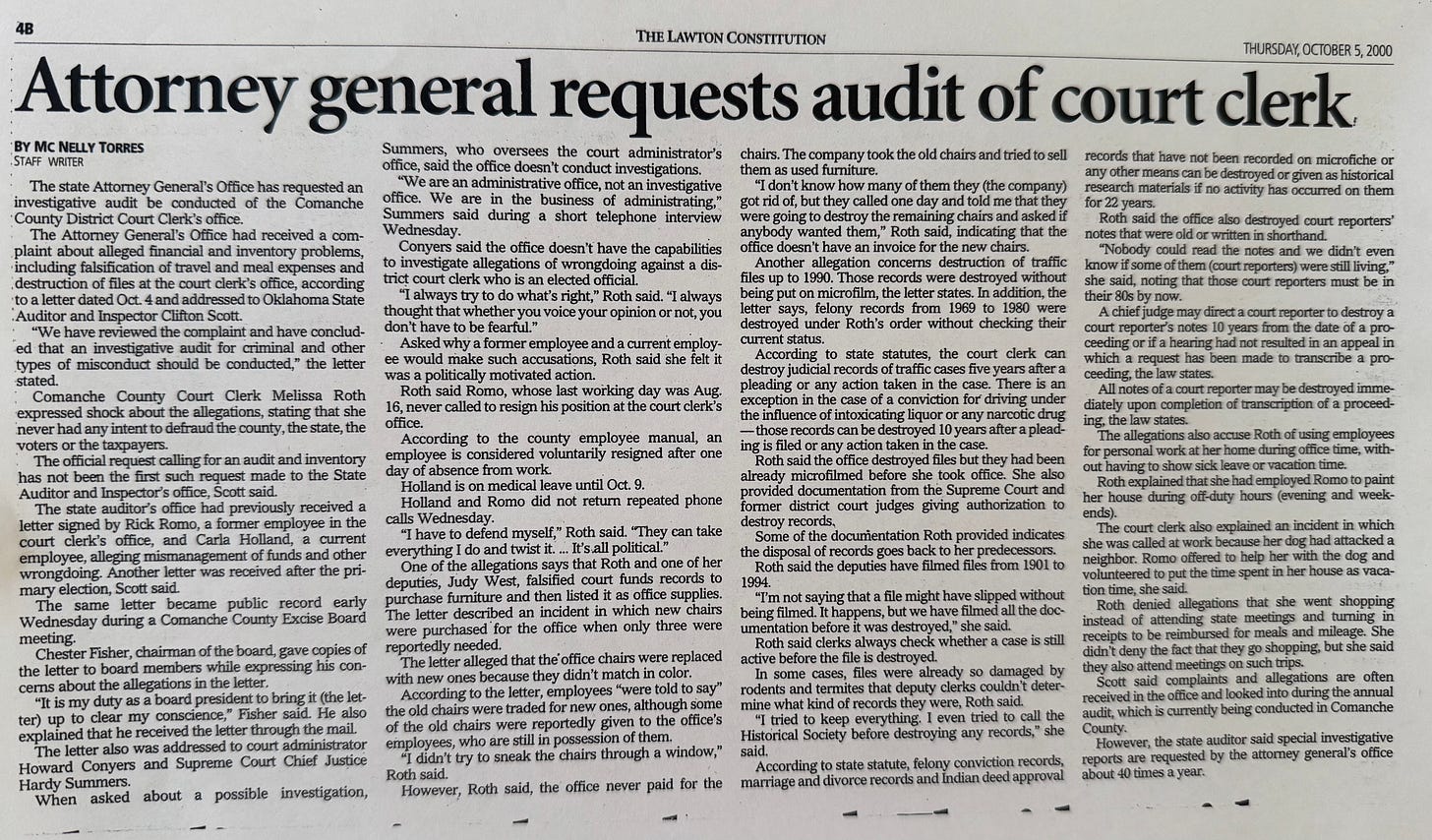

Two staff members working for the Comanche County court clerk’s office wrote a letter accusing their boss — Melissa Roth, the court clerk, of falsifying travel and meal expenses and ordering files destroyed without following state laws and proper protocols.

The letter also noted that Roth had used a staff member to work in her house during office hours in ways unrelated to official business.

This was a potential story about corruption and wrongdoing by an elected official.

The clerk’s office was someplace I visited every day on my daily crime beat rounds. Like my predecessors, I was free to walk around this large space behind the long counter. I could go among the rows of desks and explore a file room in the back next to the clerk’s personal office.

I spent a lot of time in this room, combing through felony cases I was following.

Court clerk’s offices are perpetually moving paper-pusher wheels: they receive and produce dozens, up to hundreds, of new cases (felonies, civil, marriage licenses, protective orders and divorce, and juvenile cases) that land in the system each week. Files stay until someone comes to move them out into other storage places to make room for new files coming in.

This was also the room where the clerks would come in to fetch documents and talk to me in private, giving me scoops.

Rick Romo was one of the whistleblowers and the only male working at this office. Romo was the clerk Roth sent to paint her house and do other work during working hours, the letter said.

Over the years I was there, I’d noticed some odd things during my daily visits, but nothing raised to the level for me to be concerned. I saw Romo one day with paint in his face, dark hair and shirt.

I asked what he was doing and he told me that he was painting the storage room the clerk’s office had downstairs where old files were kept. I didn’t think anything about that then; I continued doing my work, flipping through files.

But those files were the first thing I remembered when my colleague gave me the tip.

After my colleague’s tip, I called the state auditor, a garrulous, genial guy. He told me that he had received the letter and they were starting an audit. When I asked if he could fax me a copy of the letter, he complied.

The other whistleblower was Carla Holland, someone I used to chat with a lot. I dialed her home number but she didn’t answer. I left a message.

In the letter, Romo and Holland wrote that one of Roth’s deputies “falsified court fund records to purchase furniture and then listed it as office supplies.”

I silently kicked myself when my colleague told me details about the letter.

How did I miss this?

After I read the letter, I felt deeply embarrassed. It was time to interview Melissa Roth before the competition heard about this, I thought.

The managing editor didn’t support this story. “Melissa Roth is my friend,” he told me.

But I couldn’t have cared less.

This was an important story about an elected official accused of wrongdoing. She was accused of mismanaging and wasting taxpayers’ money. This could develop into a felony case, I thought.

A tense interview

I went to the clerk’s office and asked Roth whether she had time for an interview. We went into her office, which featured pictures of her family and other mementos.

I recorded the interview as I peppered her with questions about the allegations against her.

Roth denied any wrongdoing and insisted that the whistleblowers were politically motivated since that was an election year. I pressured her to respond to each allegation. She did.

The story was published on Oct. 5, 2000, on page 4B, because the managing editor wanted it downplayed, perhaps to shield his friend.

Luckily for me, those were the days when people read the newspaper. The local TV station caught it and spent the next day chasing Roth as she left the courthouse and went to hide in a friend's house.

I became the only reporter who interviewed her before this scandal exploded wide open. A week later, I wrote a followup story with a headline reading: “Investigators begin audit of court clerk’s office”

That story was also buried inside the first section on 5A.

Roth was eventually charged with felony crimes. I didn’t get to write about that because I was already gone. The embattled court clerk cut a deal with the prosecution to evade any conviction and possibly prison time and left office.

As I think about this moment now and even then, I know it would have been difficult to clearly notice that something strange was going on, even if there were signs. Perhaps I was too tough on myself.

But the universe was sending me a lesson: Just because you are welcome into a place, it doesn’t mean people have to tell you everything, or tell you the truth.

A dysfunctional family often appears perfect to the outside world, while horrible things are happening inside their home, after the doors are shut.

As journalists, we need to keep our eyes always open. We need to be inquisitive and perceptive enough to see red flags when they dangle in front of us.

This is never easy.

Seeing signals in the papers

Although some tips come by voice, some come buried in documents, when a thread in a high-profile story leads you to confront a systemic problem that needs exposing. You didn’t expect to get there, but somehow you do.

That’s exactly what happened after I covered Andrea Britt Young’s brutal killing by the father of her two children.

Comanche County courthouse clerks reminded me of the many times Young had been there with children in tow, waiting to file the paperwork for a protective order.

She was tall, with long blond hair, beautiful, hard to miss. I saw her immediately when I went to the office and saw a small crowd waiting outside.

Young and Thomas Earl Greer had a turbulent and abusive relationship. He’d beaten her during pregnancies and had violated several protective orders. He’d been released from jail for violating the most recent one.

Greer stabbed Young at least 16 times in front of her children and his mother, who took care of her grandbabies while Young worked.

This case led me to look deeply at protective orders, a legal tool that did nothing to protect Young. I interviewed attorneys, legal experts, judges, law enforcement officials and attended protective order hearings to find a loophole in the law that opened the doors for people to abuse the system.

I wrote an enterprise story exploring protective orders, which were designed to stop domestic violence and protect victims but had become a tool people used to solve conflicts outside the court system, bypassing mediation.

The extensive package was published Jan. 31, 1999, a Sunday, when the paper’s circulation was highest.

Having a good instinct for stories means being curious and asking questions when you notice patterns; they may signal trends.

During my years reporting crime, I noticed an odd pattern as I mulled over police reports — sex offenders moving to Lawton after serving time in prison and complying with sex registry laws. These laws were supposed to create a system for tracking, monitoring and notifying the public about registered sex offenders.

The problem — each report had the same home address — and not a halfway house or anything like that, someone’s house. This pattern sparked another package I eventually wrote; it showed the problems with the toothless sex offender registry laws.

Good beat reporters are always looking for good stories because they are curious, ask questions and notice trends and problems.

As a beat reporter, I covered the daily stories, but always looked for any enterprise to keep editors happy as I slowly developed investigations.

This two-level observation requires discipline, time and commitment that is developed over time, like a sixth sense, as you move around, make mistakes and find stories. Don’t be afraid to create your own system, because curiosity and ingenuity could lead you in great, if unexpected, directions.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.

Resonates now more than ever...we can't trust what we are told and are in dire need of a sixth sense