Plan, strategize and move on with a bang

As you gain job experience, you’ll learn to understand when it’s time to seek new opportunities and expand your career.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

There will be a time in your career when you decide that it is time to move on from a job — when you feel stuck and that there’s no probability to grow. I’ve been there and learned to recognize when the newsrooms have turned toxic and staying in them is worth neither the time nor the effort.

I was at this point in 2005. It had been over three years since I moved to San Antonio to work as an education reporter for the local paper, the San Antonio Express-News.

Editor turnover signaled internal problems; I had three editors during my tenure there. My second editor, a Black woman, was so good that she was promoted to features editor after a year at the newspaper.

I knew my time in that newsroom was coming to an end as I had traveled to Florida months before to interview at the Sun-Sentinel, but there was one big story I wanted to write before moving on.

I had accumulated a wealth of information about Edgewood Independent School District — one of the poorest and most fascinating school districts in San Antonio. I had enough to write an in-depth overview of this school district, its decades-long financial and political struggles and its resilience and fighting spirit. I wanted to provide historical context and use data and reporting to zoom into the community and respectfully tell its story at the present.

As I wrote in the story, the fight began in 1968 when Edgewood High School students marched to the administration office and demanded better supplies and qualified teachers.

That same year, Edgewood parents filed Rodriguez v. San Antonio Independent School District in federal court, which addressed whether using local property taxes to fund public schools was constitutional. The case set off decades of legal battles. In 1984 Edgewood parents again turned to the courts, scoring a victory when a Texas state judge ruled the school finance system unconstitutional.

This led legislators to craft what became to be known as the “Robin Hood” system, which required 134 property-rich school districts to share their wealth with low-income school districts, including Edgewood, a historically poor school district.

This system and an infusion of federal funding helped this urban school district to bring more certified teachers, start new programs to help students and school upgrades.

But divisive politics within the Edgewood school board and constant change in leadership brought instability, parental distrust and a host of problems.

I thought I was the right person to write this story because I had earned the trust of people in the community.

I spent time talking to them about the past and present and I knew how betrayed they felt about the constant changes in leadership and broken promises by a school architect.

He’d promised to renovate and rebuild schools but left after seven years, leaving behind unfinished work and costly delays.

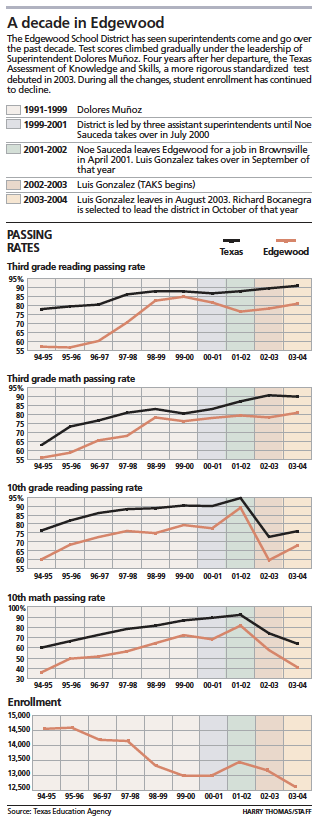

The data, which we used in a graphic, backed up my reporting. We also used student enrollment data to show how the district had changed over time and why some schools were closing.

The district lost millions in federal funding that decade as student enrollment dropped from 14,547 to 12,617. And we showed how student performance changed as the district’s leaders changed.

Remarkably, student performance improved during a time of stability under Dolores Muñoz’ tenure, who served as the school district superintendent for almost a decade. After years of rating “acceptable” — essentially average — under the state’s system, Edgewood won “recognized” status in 1999, second only to “exemplary” in the rankings.

But Muñoz didn’t stay around to enjoy that success. Bruised by fights with a new elected school board majority, she left in 1999, waving goodbye to the two years she had left in her contract, I wrote in the story.

This story was newsworthy too because Texas’ Legislature was searching for better ways to fund the state’s poorest schools like Edgewood.

My new editor, a white woman, edited the piece and gave me an unflattering introduction to her management style. I appreciated her guidance, but she was needlessly aggressive, pushy, arrogant and rude. I kept my calm and focused to ready the story for publication. That was the goal.

Sometimes, the universe sends you signals that you can’t ignore. After that story ran, I was sure it was time to seek opportunities elsewhere. I didn’t tell management I was leaving until I gave my two weeks’ notice.

The story was the centerpiece published on a Sunday, Feb. 27, 2005, on the San Antonio Express-News’ front page, above the fold with a full page inside the paper as the jump. Its headline read: Equity not enough in Edgewood.

I ended the story with a quote that summarized the essence of Edgewood.

“Edgewood is not a community that ignores education, but they have to overcome decades of racism and neglect,” said Jimmy Vasquez, who was Edgewood superintendent when the lawsuit was filed. “How can you undo 100 years of neglect and underfunding? We had a flawed and unfair system that denied the most basic right to colored children and this is a deep, deep wound that would take time to overcome.”

This piece was my farewell to the school district I covered for three years and its wonderful community.

This story was part of my strategy: plan, execute and depart with a bang.

When is time to go

By the time I left the Express-News, mid-April 2005, I’d produced an extensive portfolio of investigative and data-driven work on education. My stories sparked the conviction of a school building architect accused of bribery.

But I realized that the paper, for me, wasn’t someplace I could grow and move up the professional ladder.

It wasn’t always so. I’d felt awe when I interviewed with editors spring 2002; I had never seen so many people of color inside a newsroom. But appearances could be deceiving; I’d discover the newsroom was a reflection of a city where the power structure has always been white.

Larry Graham, founder and executive director of The Diversity Pledge Institute, a nonprofit group devoted to helping newsrooms diversify their staffs, told a group of journalists in May that there’s no valor in sticking around a newsroom when the writing is on the wall that you need to leave.

Graham compared a bad job to a bad meal.

“In these types of situations where we’re feeling marginalized, we’re feeling downgraded, we go for a second bite, a third bite, we’ve eaten half that sandwich. That doesn’t make any sense to me,” Graham told the group via Zoom. “Why put up with something that’s not for you?”

Two decades later, my portfolio continues to grow as I held leadership roles as an editor and manager, including creating an investigative nonprofit from scratch and leading a team at the Center for Public Integrity. I have also continued to produce award-winning investigative journalism, one piece was a 2025 Pulitzer finalist, as I continued to support other journalists and help them excel.

These experiences taught me many lessons, including, as the serenity prayer says, that sometimes we need to find the courage to change things we can change and accept the things we can’t.

In San Antonio, I had to accept that a diverse workplace doesn’t necessarily signal a welcoming, equal culture for people of all backgrounds.

That became clear after the top leadership announced a round of promotions leaving all the people of color in the newsroom shocked and upset. The decision to promote white favorites in the newsroom was done without any transparency or a fair process to allow others to compete.

We met outside the newsroom at a colleague’s place, aired our frustrations and crafted a letter noting our concerns about the lack of process and fairness. We used the city’s demographics to show that San Antonio was a diverse city with a large Latino population and argue that the newsroom would be better served with a similar demographic mix. This message led to the promotion of my second editor — a Black woman and the best editor I had during my time there.

I was happy for her, but this was not a win for me. I realized that this was not someplace where people were valued for their work. I was not willing to play that game.

Building a welcoming and equal culture takes intention, care and commitment from those on the top; that newsroom wasn’t it.

Once I decide something, I have no regrets and don’t look back. Onward I go, and upward.

Thanks for being along for the ride.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.

Thank you for sharing your story; it took me back. Three years ago, I decided to quit a job at an organization that, on paper, shared many of my values. In practice, however, it was emotionally draining me to the point of threatening my emotional stability. I really believe there's a lot of truth in the idea that you always know, deep down, when it's time to leave a place. Sometimes fear, ego, or emotional attachment hold us back, but our bodies and minds always seem to know when it's time to go.