Handle (yourself) with care

Reporting and writing about trauma can wear on journalists psychologically; Self-care really matters.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

The phone rang close to 6 a.m. Central Time in 1998.

It was a call from Puerto Rico. I was happy to hear Edward, my childhood friend, on the other end of the line, early though it was. As it happens with such calls, I knew he was about to deliver bad news.

“Sit down, Mc Nelly,” he said. “I just heard on the radio that Indo was killed last night.”

Edward had been driving to work when he heard the news on the radio. He quickly stopped at a newsstand to grab a newspaper and read the details, he told me.

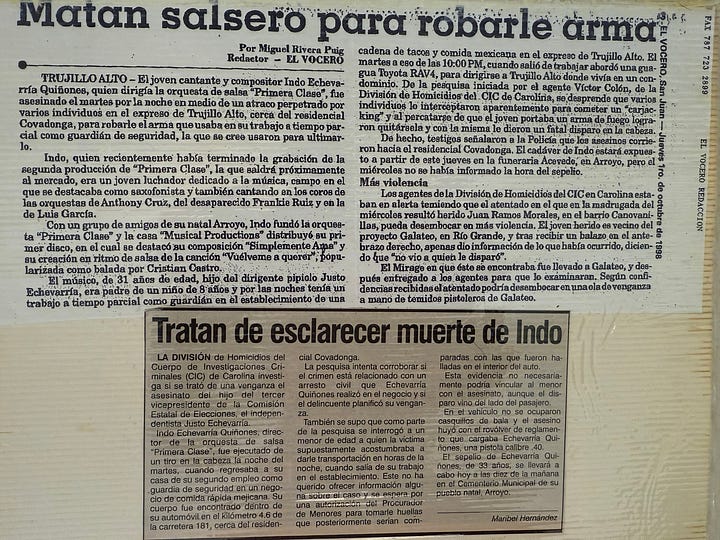

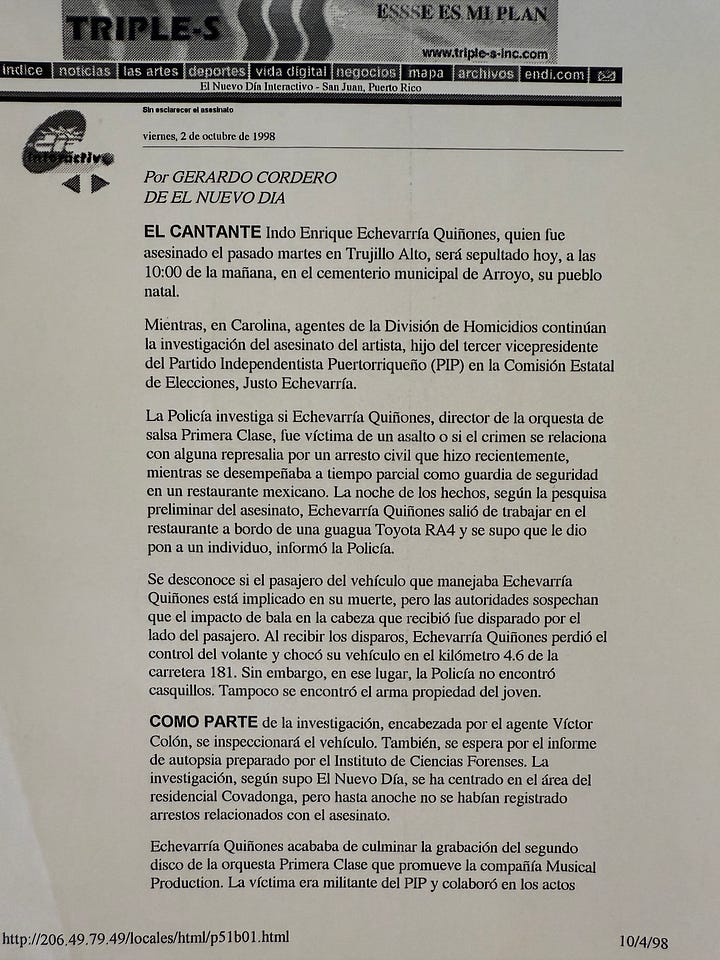

El Vocero, a daily tabloid, published a front-page story and picture of 33-year-old Indo Enrique Echevarría Quiñones as police found him, in his car’s front seat, shot in the head.

Indo was a childhood friend, a gifted musician, music writer and a father of a young boy, named Ravel after the 1928’s Boléro de Ravel.

His tragic death shocked both my native town of Arroyo, Puerto Rico, and our large network of childhood friends, including my husband. The tight-knit network included musicians, singers, and dancers — all former members of Copani, an arts program in Puerto Rico.

I met Indo, who was several years older than I, when we were in the high school band in Arroyo. I was in middle school and the group’s youngest clarinet player.

After Edward’s call, I called my husband at work and gave him the bad news. Then I took the kids to school and went to the newsroom. When I got there, I found my colleagues already knew my news; my other friends from the island had called asking for me.

I had so many questions, chief among them: Why was he killed? Who did this?

I called El Vocero, introduced myself and kindly requested a copy of the story by fax. In those days, faxing was the fastest way for me to get it.

Indo had left his gun resting on the passenger’s seat. As he approached a traffic light, the teen grabbed the gun, shot Indo in the head and left him there, investigators later revealed.

Police found Indo’s lifeless body on the driver’s seat. The vehicle was at a traffic light and the passenger’s back door was ajar, according to accounts at the time.

I received the faxed copy of the story without the picture. I appreciated that. I’ve seen plenty of violence as a crime reporter, including an execution by lethal injection. But, this was personal. Indo was someone whom I’ve known since I was 12. And though I was far away, I wanted every detail I could get.

Though we were sad to lose our friend, my husband and I decided to skip the funeral. We couldn’t afford the cost of travel to Puerto Rico for our family of four.

We wanted to remember Indo the way he was when he was alive — free spirit, risk taker, funny, talented, loud laugh.

So, time and life go on. So did I, taking care of everything and everybody but myself. Not wise.

Having good sources as a crime reporter in Oklahoma, access to information and sometimes gruesome crime scene imagery comes at a high cost.

Years later, I can still picture the toddler who landed in a creek after his mother, who’d been holding him in her lap, fell asleep behind the wheel. She lost control, veered off the highway; the car crashed down the hill and fell into the water. The baby drowned.

Or the young woman who gave birth in the backseat of her best friend’s vehicle, put the baby in a trash bag and tossed both into a trash bin behind a church.

Months after I left Oklahoma, I began to understand that I was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). I was depressed, gained weight and maybe I drank too much.

A call from someone I met in the Netherlands became my own reckoning — I needed to mourn Indo’s death and feel the trauma reporting I’d been exposed to during my 4.5 years on the crime beat.

I couldn’t move on until I made peace with everything, including a beat I found addictive and intoxicating. Years later, I understand that suppressing emotions to get by, as I did in newsrooms, carries a high cost. I had former colleagues die by suicide, heart attacks, cancer, substance abuse and alcoholism.

Researchers have spent decades documenting the effect of work as we do as journalists, often witnessing violent news events. “Covering trauma, as we do in our jobs, can generate another kind of trauma,” said Natalee Seely, an assistant professor of journalism at Ball State University.

“Like therapists — who through the process of ‘transference’ can vicariously experience their patients’ emotional pain — reporters may also experience a type of indirect, secondary trauma through the victims they interview and the graphic scenes to which they must bear witness,” she wrote on a 2019 study on the impact of covering trauma published in Newspaper Research Journal.

A survey of 30 journalists conducted after Hurricane Harvey in 2017, found that 1 in 5 respondents met the threshold for PTSD, and 90% experienced some level of PTSD symptoms related to Hurricane Harvey coverage. Two in 5 respondents met the criteria for depression, and 93% experienced some symptoms of depression, the survey showed.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many journalists began looking at our business internally as we covered massive numbers of deaths all over the country. It was eye-opening, because journalists began sharing experiences about how they learned to cope with trauma.

Journalists know this job is not easy and its challenges never stop. We can’t survive if we don’t take care of ourselves. Newsroom leaders must support their staffs’ psychological well-being and change the “suck it up” culture that has plagued newsrooms for far too long.

Here are some self-care tips, recommended by experts, that I’ve adopted over time and some of the things I do to take care of myself:

☕️ Take a breather and step out. Sometimes you can’t control what’s happening around you, and that’s okay. But you can take a break and remember to breathe.

🌺 Have rituals to end your working day. I always end my workday by cleaning the makeup from my face and changing clothes even if I’m working remotely. It’s how I say to myself: “I’m done with work now, time for me and my family.”

🚶♀️Take time off after wrapping a big project or a story. I try to take a day off after a big project is published. I also clean up my workspace because that to me means new beginnings.

🥗 Adopt a healthy lifestyle. You can’t function if you don’t sleep and eat well. Long walks or any type of exercise and healthy meals should be part of your daily routine.

📵 Disconnect from email and social media. Disconnecting from technology can be invigorating. I did that after the election, especially avoiding TV news, and it did wonders. I still do this on weekends. (No “Meet the Press,” “This Week,” “State of the Union,” “Face the Nation” or “Fox News Sunday.”)

🧘 Mentally prepared before reporting a tough story. I’ve been practicing yoga since 2017. While attending the NICAR conference in Jacksonville, Florida, my friend Paula Lavigne, an investigative reporter with ESPN, mentioned hot yoga. I came back home, tried it and was hooked. It changed my life; it made me aware of my body and helped me decompress. The sweat felt like cleansing — I was washing away the stress.

🤝 Build a community outside journalism. I don’t hang out with journalists on the weekends or on holidays. You need a space where you are not talking about work.

💃 Find a hobby that makes you happy. I love to dance salsa. I’m a yogi but I’m also a doggie mom which means my dog keeps me active when I walk her during the day on work breaks. I love to cook and that’s something I do with my family at home. Find something that makes you happy so you can relax and be yourself.

Mourning is a journey

The aftershocks from Indo’s death resonated for many years; I always remembered the day I got Edward’s call. But as I continue my journey, raising a family and producing journalism, I’ve slowly moved on.

I accept now that death is part of living.

When I visit with friends in my hometown, we always remember Indo fondly. We laughed about his craziness and reminisced about being in our teens. We repeated the stories we told ourselves a thousand times. We also support the foundation (Fundación Indo Echevarría) his father, Justo Echevarría, created to celebrate his passion for music.

That’s how we remember and honor him.

Eventually, I left Oklahoma, and the crime beat. I moved on to cover other interesting beats that let me expand my horizons and grow as a reporter and investigative journalist.

Although I continued to cover complex, difficult topics including natural disasters and human suffering, I know my psychological limits. I know I need to balance my personal and professional lives. They’re not the same.

I take time to travel, laugh, dance, eat and visit people I love.

Life is too short not to.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.

As I was reading your story I could recall in my mind the picture of Indo lying dead in his car… I cannot imagine the trauma reporting this tragic stories creates in reporters, but as hard as it is it needs to be done! I am glad you found ways to deal with it. Thanks for honoring him!

As I was reading your story I could recall in my mind the picture of Indo lying dead in his car… I cannot imagine the trauma reporting this tragic stories creates in reporters, but as hard as it is it needs to be done! I am glad you found ways to deal with it. Thanks for honoring him!