Diversity in newsrooms still a myth

A 1996 study unveiled during the Associated Press Managing Editors convention in Denver about race relations in newsrooms has remained relevant over the years.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

I was a college senior the first time I wrote about the racial tensions in newsrooms in the United States.

It was during my last semester at the University of Southern Colorado (now known as Colorado State University, Pueblo) when I was selected to be part of the APME Gazette’s staff, a student newspaper, covering the 1996 Associated Press Managing Editors convention in Denver.

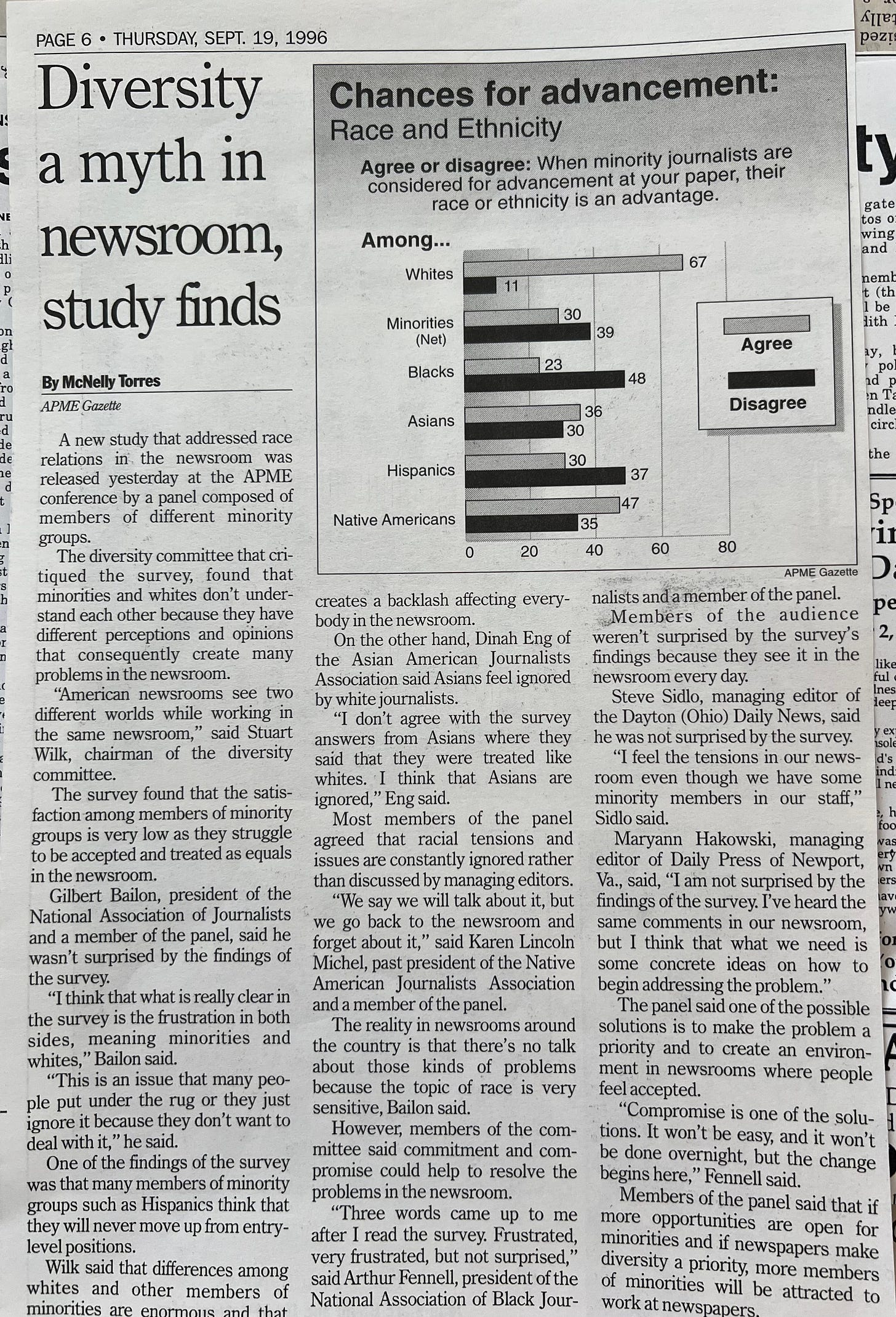

The article revealed the results of a survey conducted with participant newsrooms in the U.S. It found racial tensions among journalists of color and white journalists.

Journalists from different affinity groups discussed the survey at the conference, noting how groups, across racial lines, didn’t understand one another because they all viewed the world differently. And these cultural differences, the article said, were creating many problems in newsrooms.

The survey also noted that management often ignored the racial tensions rather than facing and discussing them openly. Not surprisingly, the survey showed that newsroom satisfaction for journalists of color was very low “as they struggled to be treated as equals in newsrooms.”

As I look back at my career, I can see how this article foreshadowed what awaited me as a Latina journalist.

But here's what everyone misses about diversity, equity and inclusion — it’s totally achievable if you have the collective will and courage to do the work. I’m not going to sugarcoat this, it is work. Hiring and promoting all types of folks is just the beginning.

Newsrooms must build a healthy environment and culture in which people are willing to talk honestly and respect one another. Nothing works without the aim to build a strategy with clear goals and measure progress. This is the method newsrooms use to tackle big projects, and it’s the method for achieving DEI success.

But building a welcoming culture might not be a priority when newsrooms are facing so much financial uncertainty.

I experienced this at my last newspaper job in Florida — the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Although it was one of the most diverse newsrooms I’ve ever worked in, it still had resentful, racist people who were not shy about expressing discontentment about their Black and brown colleagues.

I blamed managers for the toxic culture. They failed to build a newsroom that was inclusive and welcoming. They failed to include people in decision making, hiring or policy.

Newsrooms benefit from having the proper representation on the communities they cover — they can cover marginalized communities with depth and understanding, avoiding superficial coverage that could offend those communities. Inclusive newsrooms and the coverage they produce can also increase audience numbers and engagement.

This approach shows in the reporting. In 2022, Neiman Reports found that newsrooms relying on past methods or newsroom leaders’ gut instincts risk amplifying unconscious biases. But, the study said, collecting readers and viewers’ opinions and letting those opinions shape editorial decisions can help newsrooms state unspoken assumptions, recognize underlying biases and better choose what gets covered.

Not all of my former colleagues have welcomed these ideas. People tend to resent being forced to try things that make them uncomfortable, however briefly.

Over the years, I have discussed some of my experiences while working for the Tribune Co. with several of my former colleagues. We have traded stories about racial microaggressions from white colleagues and the reaction after layoffs, which affected mostly people of color.

I didn’t realize how bad the racial tensions were in this newsroom until I moved from the Sun-Sentinel’s Miami Bureau to its headquarters in Fort Lauderdale after I joined a newly created consumer team.

Some people (mostly white women) told me I was there because I was a Latina — code for affirmative action. The rudeness of these comments surprised me and I often wondered: Have these people seen my résumé?

When the managing editor who was hired to diversify this newsroom announced her retirement, a white male reporter smiled widely and said to me, “No more diversity.”

By the time the 2008-09 financial crisis hit South Florida and newsroom layoffs began, we journalists of color suspected that many of our former colleagues (presumably the white ones) were calling us “incompetent minorities” or suggesting that we “should apply for jobs at McDonald’s” in anonymous comments under stories about newsroom layoffs.

We endured several layoffs that went on for a year. All the people who hired me, and many of my mentors and friends were gone before me. When I was laid off in May 2009, ugly comments appeared under the story about the staff cuts. One said, “She walked around like she owned the newsroom.”

It didn’t matter that I had investigative and data skills or that I’m bilingual. It didn’t matter that I’d worked as a beat reporter in four dailies before I came to Florida. It didn’t matter the awards I’ve garnered or that my work had made lasting impact in the state.

What mattered to these people were my ethnicity, gender and the way I walk.

That’s how hate works.

I’d never been laid off before. I was devastated but somehow relieved because the unhealthy environment and the financial uncertainty was taking a toll.

I felt sorry for the people who spent the time and energy posting hateful messages under the cloak of anonymity. Some of the stories are still available and although the comments are gone, I remember them.

Achieving newsrooms in which people feel welcome, respected and heard won’t happen overnight. Bad actors need to be called out and people need to confront and acknowledge the past, no matter how ugly it was. Newsrooms that build inclusivity will make mistakes, but they’ll also probably see progress.

It’s all part of the journey.

DEI exists for a reason

Congress passed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because there were people in America who discriminated based on race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, age, and disabilities.

This is true in society and workplaces, including newsrooms. Throughout U.S. history, journalists of color have faced racism and discrimination in newsrooms similar to what Americans of color have faced in broader society.

Data shows this problem still exists. A 2022 Pew Research Center poll of almost 12,000 journalists found that 68% of journalists ages 18 to 29 said there wasn’t enough racial and ethnic diversity at their organizations, compared with 37% of journalists 65 and older. Fifty-seven percent of polled journalists ages 30 to 49 said their newsrooms lacked sufficient racial and ethnic diversity, Pew found; 48% of journalists 50 to 64 said this.

White men — and women — have traditionally led newsrooms, told us how to define and produce journalism and selected those producing investigative journalism.

Many newsrooms likely reckoned with race in 2020, after a white police officer killed George Floyd, an unarmed Black man. But the reflection was evidently short-lived. And in May, my whole newsroom at the Center for Public Integrity, the most diverse investigative newsroom in the country, was let go.

This puts the whole DEI concept debate back at square one. An October 2024 Institute for Independent Journalists study showed that layoffs affected marginalized journalists — women, journalists of color and younger professionals — the most.

We are in the second month of 2025 and the job losses have continued as the media battles to exist in a digital ecosystem rife with mis- and disinformation.

Also, Donald J. Trump is back in the White House, calling to end DEI and blaming DEI for disasters, notably a deadly crash between a U.S. Army helicopter and an American Airlines jetliner. Corporate America and some media outlets, responding to Trump’s call, have dumped DEI programs.

Things don’t have to be this way.

Finding that article about the 1996 study amid my old clippings didn't give me much comfort. But I saw it as the universe sending me a message.

The struggle to achieve DEI is not over. Fight on.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.

Yes to everything in this newsletter post!!!! I met you in person while I was part of the local NAHJ chapter and during my (brief) time in journalism, I witnessed similar things—albeit on a "microaggression" form, like being told I filled the "diversity quota" and getting the "spicy Latina" label during a verbal performance review (yep, even back in 2018!). Sometimes it's wild to see how "two steps forward, three steps back" the journalism industry can be, and even though I'm not working in newsrooms anymore, I'm always up for supporting fellow journos who go the independent route <3