Cookie Monster broke my daughter’s heart

A crime reporter discovers that her job could affect her family in the most unusual ways, including her young daughter, a Cookie Monster fan.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate the journalism’s chaotic, toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a long-time investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

My 6-year-old daughter seemed upset when I parked at the school parking lot one afternoon.

I was there to drive her to ballet lessons, something I could do the days I worked the dayshift at the newspaper.

“Mami. I need to talk to you,” Nelly, my only daughter, announced with a serious tone after I parked in front of the ballet studio.

Her small frame stood up from the car seat, reached into her jeans pocket and pulled out a scrap of newspaper she had folded into a tiny, pocket-size piece.

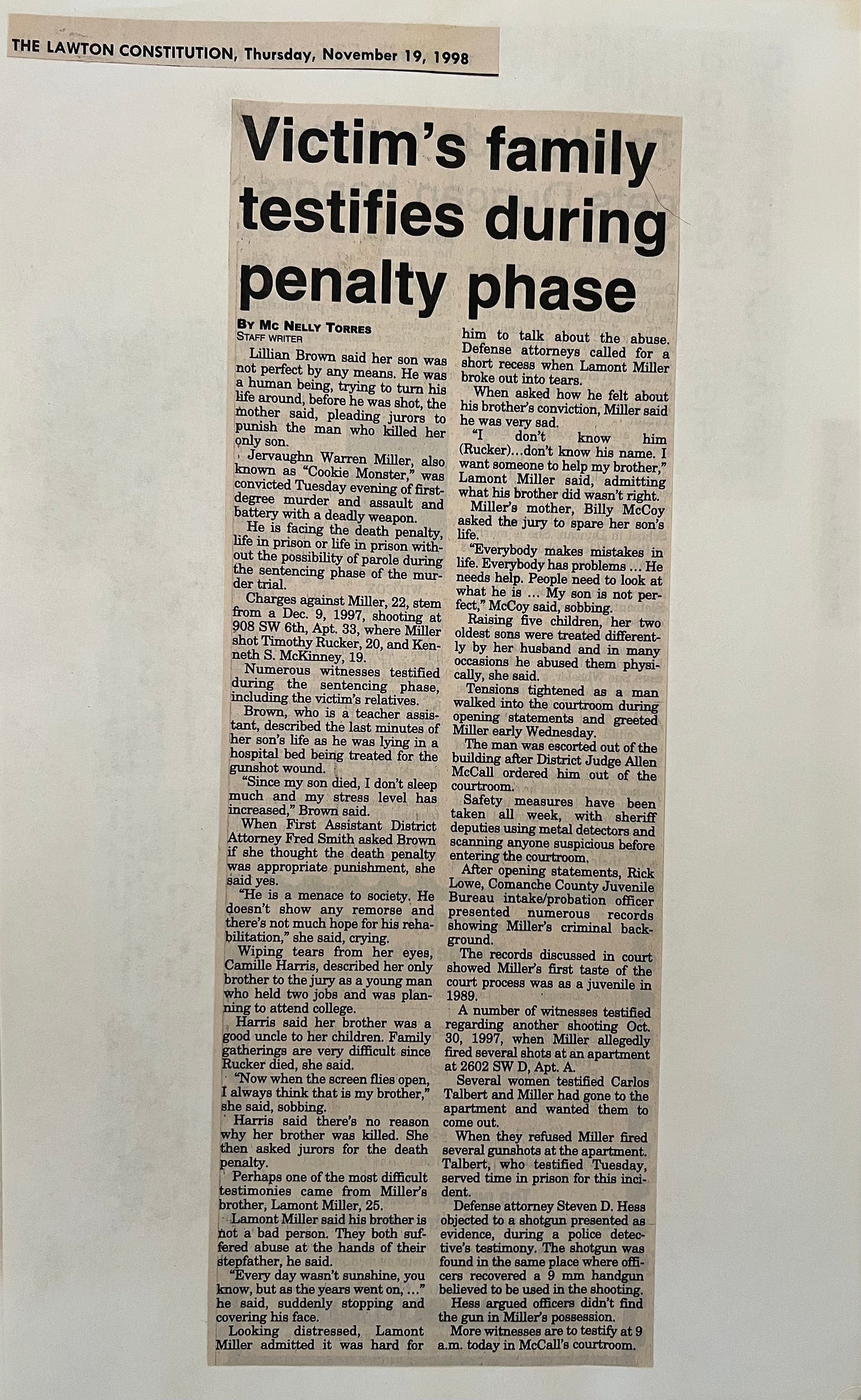

“Mami. What is this?” she asked while unfolding the piece of newspaper she had ripped from a page at school. Then she read: “‘Cookie Monster’ found guilty of murder … by Mc Nelly Torres?”

Her big blue eyes looked at me in disappointment as she awaited my explanation.

At that age, my daughter had no concept of what journalists do and especially reporters covering the criminal justice beat.

I felt deeply guilty.

I explained that this was not the Cookie Monster she adored and watched on “Sesame Street.” I, too, love that Cookie Monster, and like her, grew up watching the show when I was a little girl in Puerto Rico.

This was a nickname given to a young man and he was the one in trouble with the law, I said, not the biscuit-crunching Muppet.

A troubled young life

Jervaughn Warren Miller was 21 when he was charged with shooting two men and killing one Dec. 7, 1997, during an argument in Lawton.

A year later, a jury convicted Miller of first-degree murder and assault and battery with a deadly weapon. He received the ultimate punishment — death.

But the evidence against Miller was not compelling, as I remember. It was an incident that escalated into violence between young adults after words were exchanged, tempers flared, someone took offense and someone grabbed a gun. And it became a homicide case 11 days after the shooting when one of the victims died.

Miller, a Black man, had a history with the criminal justice system. That put him at a disadvantage with any jury in a town with a deep history of racism and oppression against Blacks.

As a court reporter who spent several years in this community, I witnessed the inequities within a system that touted itself to be just. As I covered more cases and mingled with law enforcement, public defendants, prosecutors, judges, victims and those involved in cases, I realized that people who can afford a good attorney are likelier to get good representation in court.

Trials are a competition between storytellers — prosecutors and defense attorneys. Those who tell that story and present evidence in a compelling way are likelier to convince a jury to convict or not.

So, I was not surprised to discover in recent weeks that in 2001 the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals reversed Miller’s conviction and ordered a new trial.

The Court of Criminal Appeals’ opinion offered a review of the case, which helped refresh my memory.

The main reason behind the court of criminal appeals’ ruling was that Miller had lacked proper legal representation before and during the trial as he had little or no communication with his attorneys.

The criminal appeals court noted that an application for outpatient psychological treatment documented Miller saying that he “does not trust either of the two counsel representing him.” Miller had also told “one indigent defense attorney that he had no intention of dealing with his trial attorneys because one had made a derogatory racial comment about him,” the document said.

“The bottom line is the attorneys could not effectively communicate with their client, for whatever reason, and they should have sought to withdraw from representation and to notify the trial judge regarding their inabilities in this area,” the Court of Criminal Appeals’ decision read.

The new trial ordered for Miller never happened. His case dragged on for years. In 2010, he pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of second-degree murder. He received a 45-year prison sentence for that charge and was also sentenced to serve 15 years for assault with a deadly weapon.

Miller is now in his late 40s. He has spent more than half of his life in prison.

Imagine that.

As journalists, we witness and document history, but we’re not supposed to opine about what we cover. We are supposed to suppress our feelings, or at least not express them. But journalism evolves and so do we.

Given Miller’s example, or many others, it’s not hard to understand how our work has inadvertently contributed to an unjust system that profits from inequality, racism, poverty and discrimination.

When words inflict pain

I saved my daughter’s scrap of paper for years to remind me of that moment when she taught me that my actions, whether intentional or not, have consequences.

As we ride along in daily journalism’s fast-moving car, reporting, writing and editing against the ticking clock and looming deadlines, we sometimes forget details that are important.

But, sometimes, we need to stop and consider what we are doing and why we’re doing it that way. We need to think for a moment about whether our methods and products could hurt marginalized communities and our families.

We need to ask ourselves: Is there a better way?

In hindsight, my paper should have been more diligent about the words we used in the Miller story’s headline, but to be fair that was not part of the culture there in those days.

It was all about the rush of getting the story done and “into bed” as we used to say in the newspaper business.

Years later, I would confront other situations that would remind me how my job could put my family and me in harm's way.

But that day, my daughter taught me a valuable lesson — that the journalism I produce affects everybody around me and especially those I love the most, my family.

Thanks for reading.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.