Building stronger stories, source by source

Writing is a necessary skill to succeed in journalism but cultivating sources and gaining their trust is what helps you get good stories. If no one talks to you, you have nothing to write.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

I walked into the Lawton Police Department one evening to review police reports when I had a tense exchange with the head of the traffic division.

The blue-eyed, blond-haired captain hated reporters and never missed a chance to be rude. He strutted confidently behind the counterlike window that stood between us and tore into me verbally after I requested a copy of a vehicle crash report.

I stayed cool and kept my professional composure, because if you don’t, you are giving power to the person who’s shouting and ranting. But something caught my eye — he was holding papers and making copies.

Each time he waved the papers, I would see words: second-degree murder.

Second-degree murder.

I suspected this was an arrest warrant for second-degree murder. I went through the stack of police reports looking for any leads.

It was clear to me that the captain was in no mood to cooperate and any effort to pry information from him would be a waste of time.

I had another option, so I went back to the newsroom. I shared the information with my city editor, walked to my desk and called the head of the homicide division, Maj. Harold Thorne, at home.

"Hi, Maj. Thorne. This is Mc Nelly Torres with The Lawton Constitution,” I said. “I want to apologize for calling you home at this hour, but I was at the police station and saw a warrant of arrest for second-degree murder. Are you guys arresting someone on second-degree murder tonight and who is this person?"

Journalism requires a set of skills beyond writing to get good scoops and investigative stories. You’ll need to notice details others might ignore, think on your feet, listen, and ask the right questions. But successful journalists understand the value of earning sources’ trust to have access to important information.

Thorne could have said, “Come to the police station in the morning and I will give you the story.” But he didn’t.

Because we had a good relationship, he gave me the information to write a front-page exclusive story about the arrest of a young man who was accused of strangling his stepfather to death to collect life insurance.

Sometimes, a good source is all you need to get a good story and beat the competition. And building that source requires contact, care and time.

Building a network

We say in journalism that cultivating sources is an art because it requires a time commitment as any relationship does. Good journalists, especially investigative journalists, know this. But journalists need to be transparent with sources and draw clear rules from the beginning to earn sources’ trust. I will discuss rules and ethics in the future.

As a crime reporter, I learned that building a diverse source network was a good strategy. It was intentional and aimed at casting a wide net.

After I began this job covering criminal justice, I faced many challenges because one of my predecessors had burned many bridges with the police and fire departments. Sometimes, you pay for the sins of the past.

But I didn’t let that deter me. It took me about a year to gain trust and build sources all over the Lawton Police Department and the top brass couldn’t find the leaks because they were everywhere in the building.

I had eyes all over my beat: court clerks, courthouse staff members; officials at the juvenile bureau and sheriff’s department (including the county jail); and 911 dispatchers. I never stopped building sources, including spouses or immediate relatives, because in small communities such as Lawton, police are married to nurses, teachers, 911 dispatchers and airport workers.

Yes, airport workers. My airport source helped me get an exclusive story after she gave me information about two German women who were scheduled to arrive at Lawton’s airport.

When Christa and Karina Noack arrived in Lawton on Feb. 20, 1999, I was the only person who welcomed them with a bouquet of flowers, something I learned while living in the Netherlands in the late 1980s.

Christa and Karina — mother and daughter — traveled from Darmstadt, Germany, to meet two small children, their slain mother, Andrea Britt Young’s only other kin.

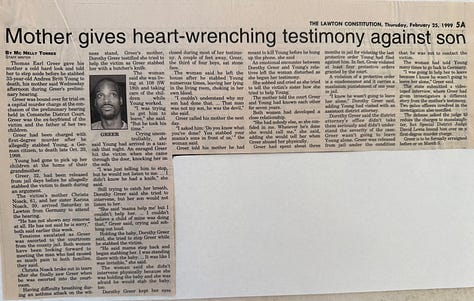

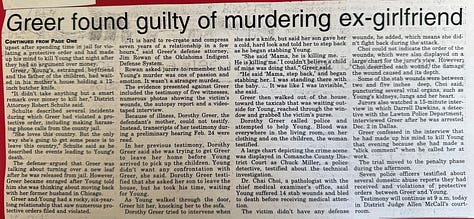

Young was brutally killed Oct. 29, 1998, by Thomas Earl Greer, the father of her two young boys. Young had struggled with an abusive relationship with Greer since 1995; he had beaten her repeatedly, including during her pregnancies. Greer was 32 when the couple split and had violated at least four protective orders.

Greer had been in jail for violating a protective order, again, but was released just days before the killing. He sat at his mother’s porch and waited for Young to come collect the children after her workday.

When Young, who was then 33, walked through the door, Greer was inside waiting for her — he hit her and she landed on the sofa.

When she testified in court during a preliminary hearing, Greer’s mother, Dorothy, said she tried to intervene when she saw her son holding a knife. But, Dorothy said her son shot her a cold, hard look and told her to step back as he began stabbing Young. Greer stabbed Young at least 14 times in front of his mother and children.

Even today, I remember Dorothy’s emotional testimony and how she had to stop between sentences and gasp for air. She described in vivid detail how she was holding the baby when this happened, and how she stood watching in horror as Young screamed for her life.

“She said, ‘Mama, he is killing me. … He is killing me!’ Dorothy testified. “I couldn’t believe a child of mine was doing that.”

Christa lost her youngest of five daughters that day; Karina lost her sister.

Finding story

I gained instant access after I received the two women at the airport. The two women had come with a foreign correspondent for Radio Television Luxembourg and a TV crew, who would document the journey and publish a TV magazine-style story.

The women were on a mission to get custody of the children, both boys, and placed in foster care after their mother’s killing.

It was a difficult interview when we arrived at the house Young had rented and lived in with her children, who were then ages 2 and 6 months old, after she ended the abusive, violent relationship with Greer. Christa, who spoke no English, walked around the front yard quietly. She touched the mailbox as she tried to imagine her daughter living there and raising her children.

“She (Young) said she was scared because he (Greer) was always coming to the house and she didn’t want to have him around anymore,” Karina Noack told me. “But he would not give her any peace.”

I wrote a feature about their crusade to confront the man who shattered their lives but also the mission to meet the children they had seen only in photographs and to ask the family court to grant them legal custody.

The family had spent months trying to get the local government to answer lingering questions:

Who will gain custody of the children?

Did they need legal representation?

How much would an attorney cost and who would pay?

The Noacks were not wealthy, but they lived comfortably and would be able to care for the children in Germany.

After the story was published, the Noacks received an outpouring of help from strangers. A local community group raised money, donated clothes and toys for the young boys.

At family court, Greer, who was convicted of first-degree murder in 1999, relinquished his parental rights and Karina, the boys’ aunt, received custody.

As the women left the courtroom, Christa faced the man who killed her daughter and asked in German: “Why?”

Greer shrugged his shoulders as if he had no motive for his actions or simply didn’t care, Christa told me later. It’s the only way I could have known this because the hearing was closed to the public.

“I would rather have my daughter alive, raising her children with him (Greer) than taking the children away,” Christa said, as her daughter translated her German words into English.

Successful beat reporters know that fostering short- or long-term relationships is important for obtaining exclusive, insightful information and building good stories.

This requires flexibility and time. Sometimes, you need to show up, no matter the day of the week or time, ask questions, listen and observe to show you are invested in telling the story.

It’s worth the effort, even if you struggle.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.