A trial, a map, a hero and a pair of indelible memories

A young reporter sets on a road trip to meet Blue Ridge mayor, a World War II hero, who was among the troops that liberated the Dachau concentration camp in southern Germany.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

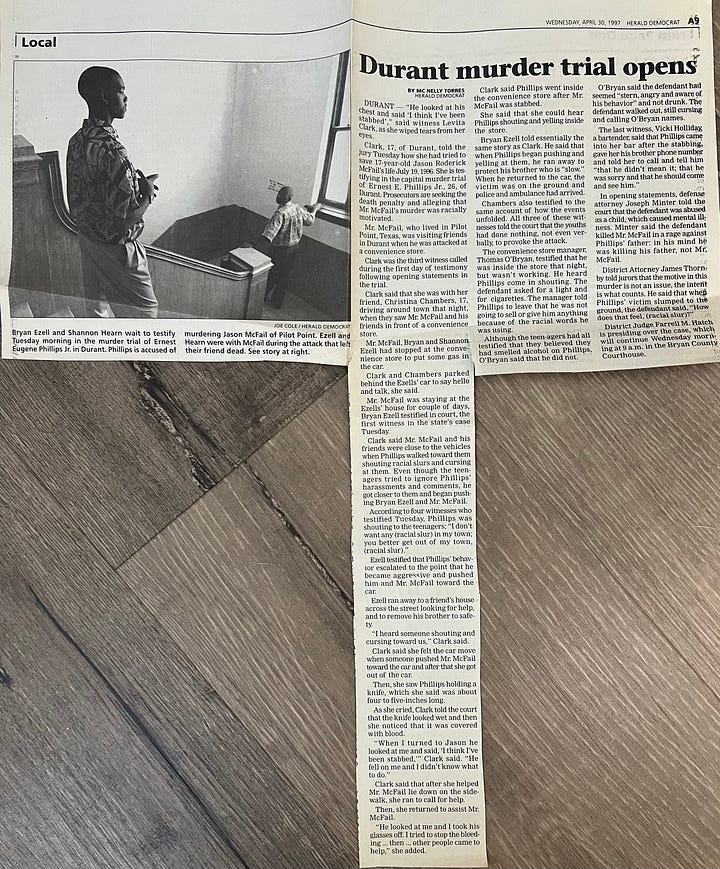

I was just four months onto my first full-time job as a reporter at the Herald Democrat in Sherman, Texas, when I covered my first capital murder trial.

It was a hate crime though we were not using that term in the late 1990s.

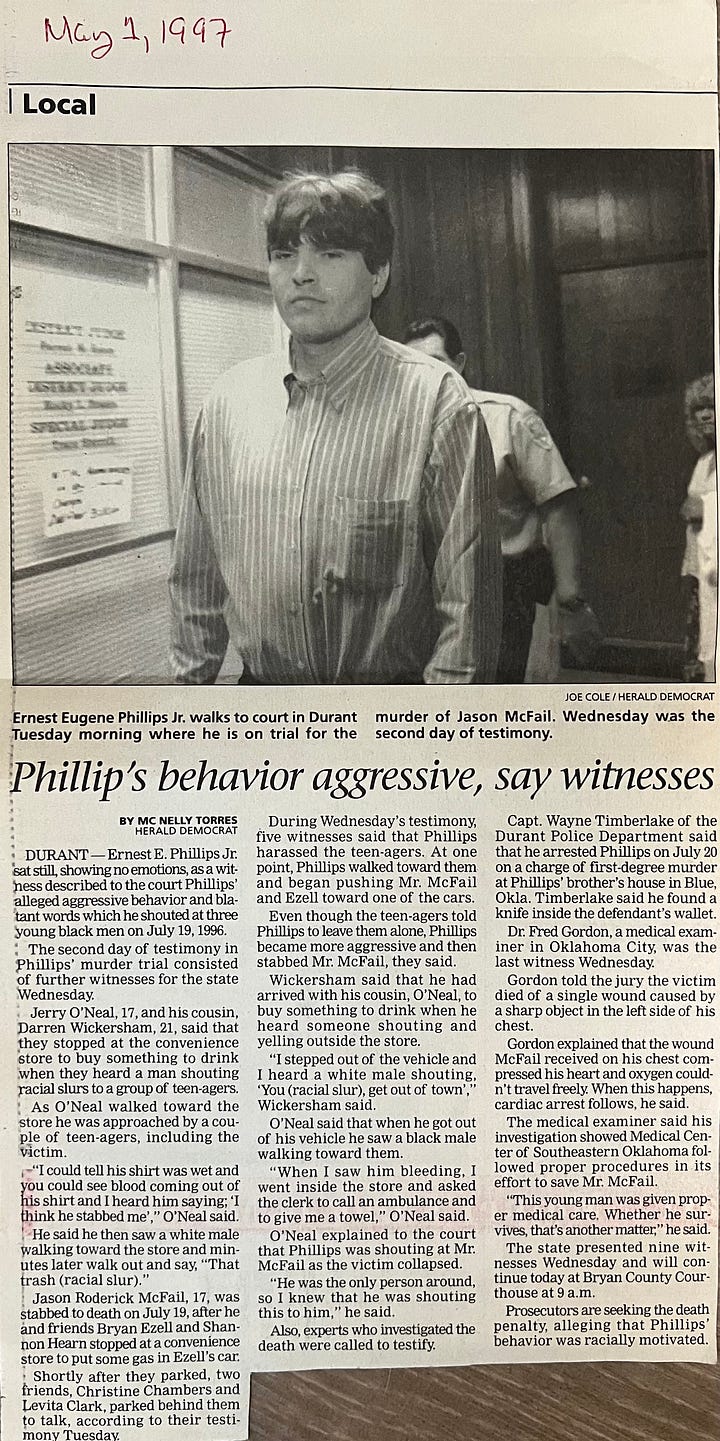

Jason Roderick McFail was visiting friends from Pilot Point, Texas, and was outside a convenience store in Durant, Oklahoma, when a stranger attacked him.

McFail was minding his own business. He didn’t know Ernest E. Phillips Jr. and according to witnesses’ testimony, McFail did nothing to provoke Phillips’ ire and hateful violence.

He was a Black teen who found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time when his life intersected with Phillips, who is white, on July 19, 1996.

Philips was angry when he saw the teens and began to shout racial slurs, including the N-word, witnesses said. Then, Phillips, who had a tattoo on his back that read, “white pride” stabbed McFail to death in front of McFail’s friends, who were also Black, and chased them off, shouting more slurs.

A life needlessly lost

Seventeen-year-old McFail had dreams most teens at his age have: driving his own car, graduating from high school, going to college and getting his own apartment.

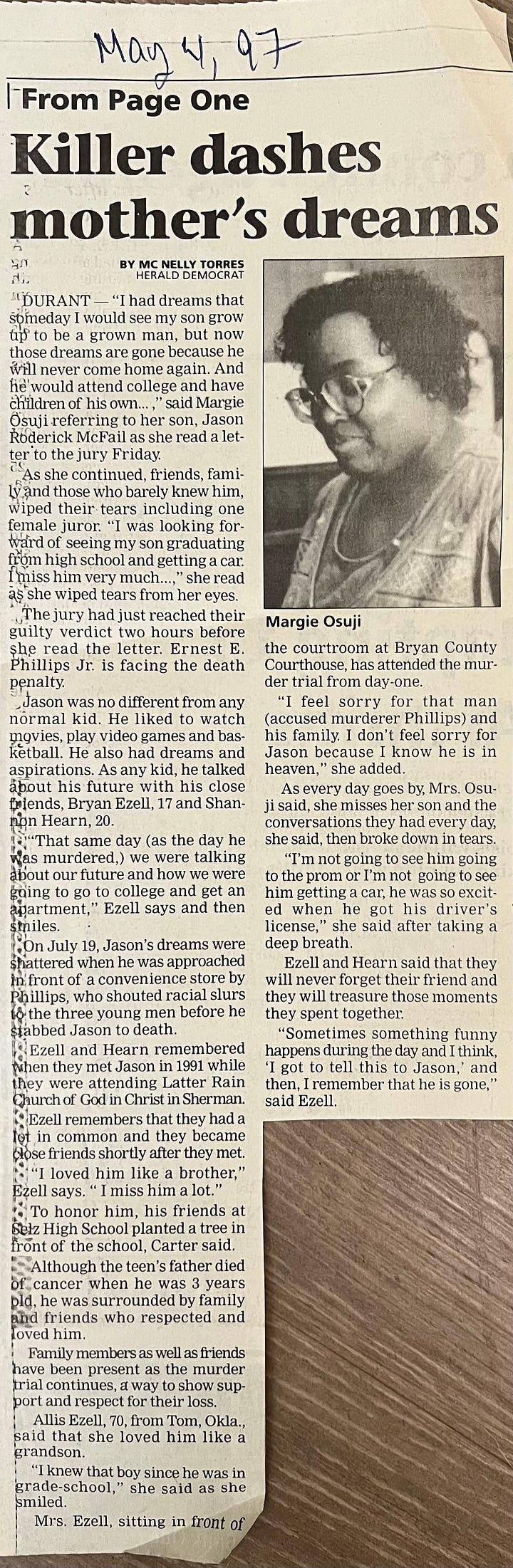

He left a mother grieving her only child. Friends and family who loved him and testified about the relationships and their close bonds and how much they missed him. Their lives would never be the same.

The seven-day trial made an impression on me as a young reporter. Two families intersected in the most horrific way. Both affected by a hideous crime.

And, at the center of this tragedy, was America’s long-rooted history with racism and racial motivated violence, especially in the South.

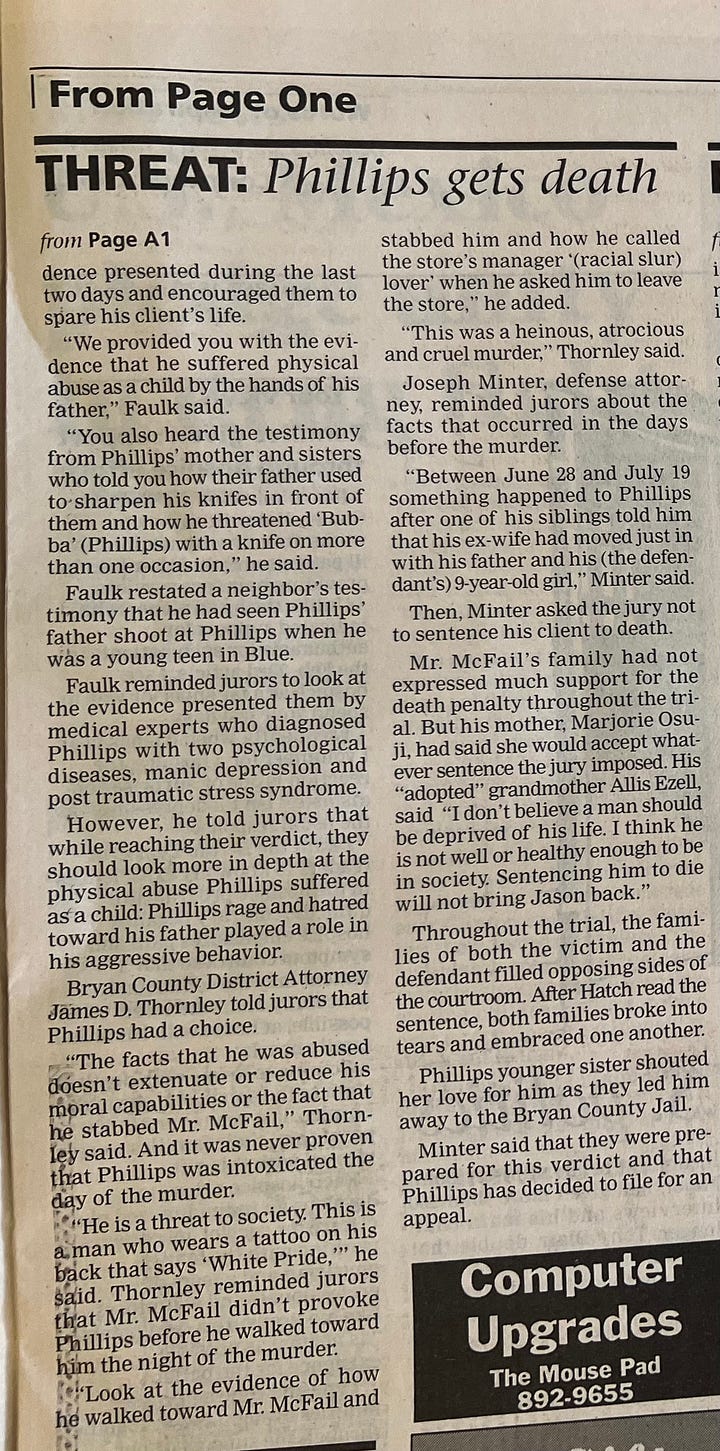

The defense dismissed testimony prosecutors presented that argued this was a violent crime fueled by racism; instead they presented evidence of Phillips as a broken man who’d suffered his father’s abuse as a child. Phillips became enraged and angry at the world, prosecutors said, when he learned his ex-wife had moved in with his father and his young daughter.

The jury convicted Phillips and sent him to death row. But in 2010, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled he didn’t get a fair trial because the court failed to allow jurors to consider second-degree murder. Phillips is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole on a first-degree murder conviction.

He is 54.

As a journalist, I joined my colleagues in gathering and reporting the trial’s information. We are not there to judge people.

But I was conflicted about the death penalty. The death penalty does not exist where I come from.

It was a long, exhausting trial. I felt sad for both mothers, families and friends. I’m a journalist, but I’m also a human being and I was already a mother of two young children when I covered this trial.

Over the years, I’ve heard people talk about closure and justice. But it’s very difficult to find closure once you lose someone you loved to violent crime. The person who dies never comes back.

New day, new assignment

A day after I finished covering the trial, a colleague called me to ask whether I’d write a feature about a World War II veteran who was the mayor of Blue Ridge, a tiny town south of Sherman.

I had no idea where this place was. There was no Mapquest or Google maps then, so I had to consult a map to learn the area and all the nearby towns and plot a route there.

Blue Ridge’s population was 521 in 1990, U.S. Census data shows, so I imagine about as many people lived there in 1997 since the population has not grown much over the years.

So, I embarked on this mini adventure and drove to Blue Ridge. I took my colleagues’ advice and flagged down a Texas Ranger on the highway, asking for directions.

As I neared the town, I felt free as the bluegrass that covers the ground like a long carpet stretching for miles and miles.

After I arrived, I entered the small City Hall building and asked for the mayor. James Burt Hedrich showed up moments later and we drove to his house, where his sweet wife was waiting for us.

I had no idea what to expect.

I had studied and written about the Holocaust while attending college including Dachau concentration camp.

But I had never met anyone who had been part of the American troops that liberated Dachau, one of the most horrendous and deadly concentration camps.

At his house, Hedrich had set up a table to show me the maps, pictures and Nazi artifacts he brought home from the war. Hedrich, then 73, had trained at Fort Hood and was later assigned to the 552nd Military Police 9th Division, which was deployed to Europe.

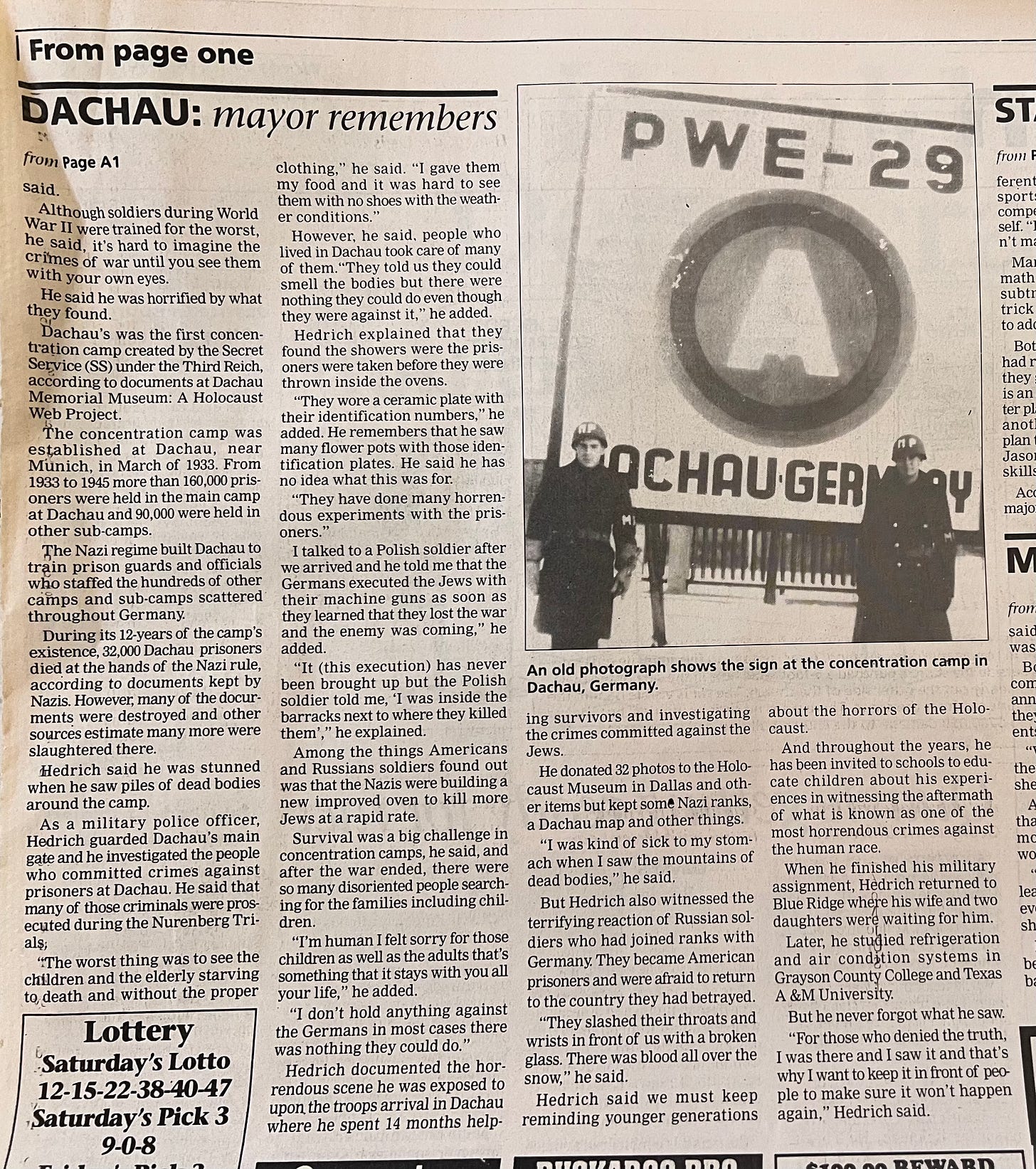

These events had affected his life profoundly. He was among the U.S. armed forces along with Russian troops, which liberated Dachau in April of 1945. Dachau was one of the first and longest-running concentration camps the Nazis built. It became a prototype for other such camps the Nazis would use to execute millions of innocent people.

Hedrich described what he saw when they entered Dachau with vivid detail: the smell of rotten bodies, malnourished adults and children looking like skeletons, riddled with diseases and without the proper clothing to protect them from the cold weather and rain. He also showed me pictures of dead people stacked in piles throughout the concentration camp.

“I was kind of sick to my stomach when I saw the mountains of dead bodies,” Hedrich said.

I’d seen similar pictures in documentaries, books and a famous scene in “Schindler’s List,” which came out in 1993 and won the Best Picture Oscar in 1994. But I had never held such a picture in my hand or talked to someone who photographed the worst behavior humanity has to offer.

“The worst thing was to see children and the elderly starving to death and without the proper clothing,” Hedrich told me. “I gave them my food and it was hard to see them with no shoes.”

Hedrich spent 14 months helping survivors and investigating the crimes committed against the Jewish people. Those cases were later prosecuted during the Nuremberg Trials.

Hedrich donated 32 photos to the Holocaust Museum in Dallas and other items but kept some pictures, Nazi uniform stripes, a Dachau map and other artifacts from a Nazi tank.

After Hedrich finished his military assignment, he returned home to his wife and two daughters. He went back to school and studied refrigeration and air conditioning systems.

But he never forgot what he’d witnessed. He volunteered his time, describing his wartime experiences to school-age students.

“We must keep reminding younger generations about the horrors of the Holocaust,” he said.

“For those who denied the truth, I was there and I saw it and that’s why I want to keep it in front of people to make sure it won’t happen again.”

That was the quote that closed my story, which ran on the Herald Democrat’s front page May 11, 1997.

As a young journalist, I felt that my writing didn’t do this hero justice. But I felt tremendously grateful for the experience.

Looking back, I realize that in mere days, I had gone from covering my first death penalty case to later meeting and interviewing a World War II hero who witnessed Nazi war crimes.

Journalism exposes you to the worst in humanity, but sometimes, it also connects you with courageous people who give you hope.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.

Love these reflections on your early days of reporting.