A delicate dance: Nourishing source relationships with clarity and candor

To avoid pitfalls, journalists know they must draw clear rules before exchanging information for stories.

Welcome back to Don’t Forget My Voice, a newsletter to help you navigate journalism’s chaotic and toxic maze. I’m Mc Nelly Torres, a longtime investigative journalist, editor, trainer and mentor.

I was two years into my education reporting gig at the San Antonio Express-News when Cliff Herberg, then chief prosecutor in Bexar County's white-collar unit, called me with information that would blow open a story I’d worked for months to report and prepare.

And I paved the path to the call by cultivating source relationships and building trust.

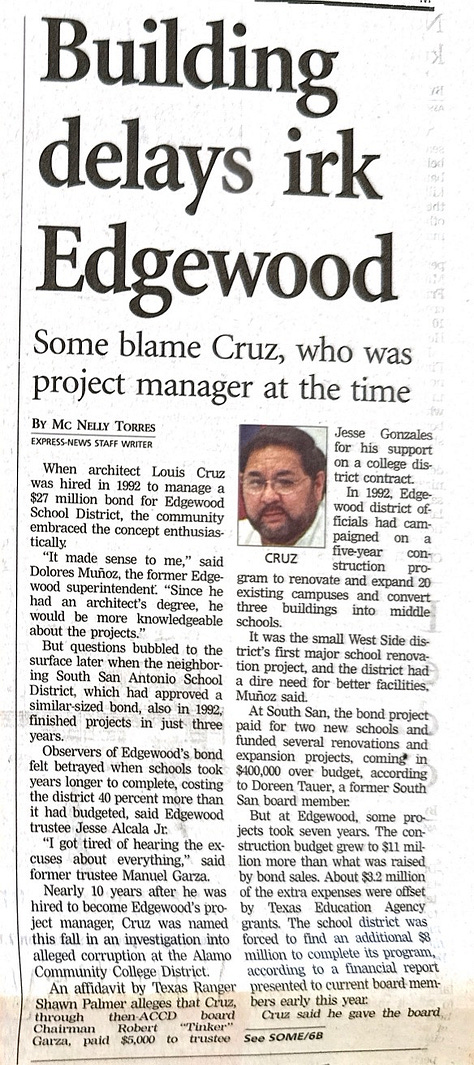

As the Express-News, I had produced several enterprise and watchdog reports about a school architect at the center of a sweeping two-year corruption probe that shook the Alamo Community College District, City Hall and some school districts.

Louis Cruz was one of nine people indicted in 2002 on bribery charges. After he pleaded guilty, prosecutors released documents with half of his confession.

Based on prosecutors’ statements, journalists in San Antonio were expecting more indictments, but it took more than a year for anything to happen.

I wanted to be the first to get the rest of Cruz’s confession. I call to Herberg’s office every other month, seeking updates on the probe and a release date for the second half of Cruz’s affidavit.

Meanwhile, I had pursued every lead and storyline possible, following the money and requesting documents. Cruz was from Harlandale, where he had allies on the school board. He began his career in school design in Edgewood Independent School District, another low-income community in San Antonio.

Months after I began reporting in Edgewood, I produced a story tracing Cruz’s early years there. The school district hired him in 1992 to oversee a five-year $27 million bond construction program to renovate 20 existing campuses and convert three buildings into middle schools. But seven years later, when Cruz and the school district parted ways, he left behind costly delays and unfinished work.

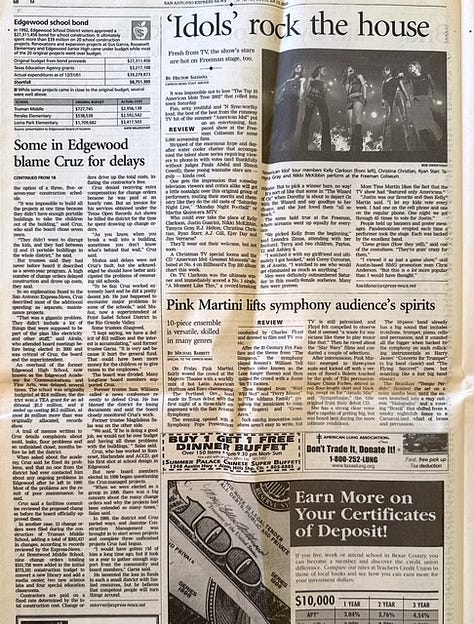

Part of my reporting was reviewing and scrutinizing then-recent construction projects, bid documents and contracts awarded at Harlandale. I discovered Cruz’s roles as an architect and project manager seemed to be a conflict of interest.

Herberg was watching my work. He’d call me every now and then to ask me what stories were coming next. I always shifted the focus to the big question:

When are you releasing the rest of Cruz’s confession?

How is the probe going?

Are you indicting anybody else and from the school districts on my beat?

When he called me on that day in 2004, Herberg sounded excited. He had been waiting for my call, he said.

I was confused and said I didn’t follow. Then, he told me that he handed Louis Cruz’s affidavit to one of my Express-News colleagues who was at the courthouse that morning and promised to deliver the affidavit to me.

But I never got the document, although Herberg didn’t know this.

"Read it and then call me when you are ready," Herberg said before hanging up the phone.

I’ve been waiting for this for more than a year, and even as large as the newsroom was, my colleagues knew this. The affidavit had been in the newsroom for hours. I knew this because I could see a colleague who had it from my desk at the end of the newsroom.

I was livid.

I walked to my colleague’s desk and asked, “Do you have something that belongs to me?”

He handed me the affidavit. Was he going to give me this ever? I wondered. What was his plan?

I love collaborating with other journalists, but sometimes I’ve come across people who are selfish and blinded by their own ambition. I understand journalism is supposed to be competitive, but common collegial courtesy goes a long way. The document my colleague had wasn’t his.

I will discuss in future newsletters how to handle toxic, unethical and unprofessional colleagues and their microaggressions.

I said nothing to him and took the documents. There was no time to waste.

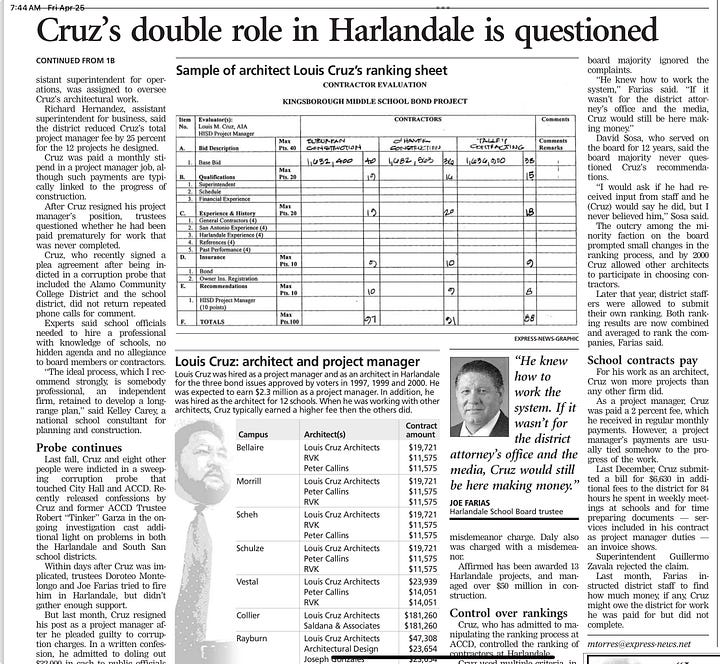

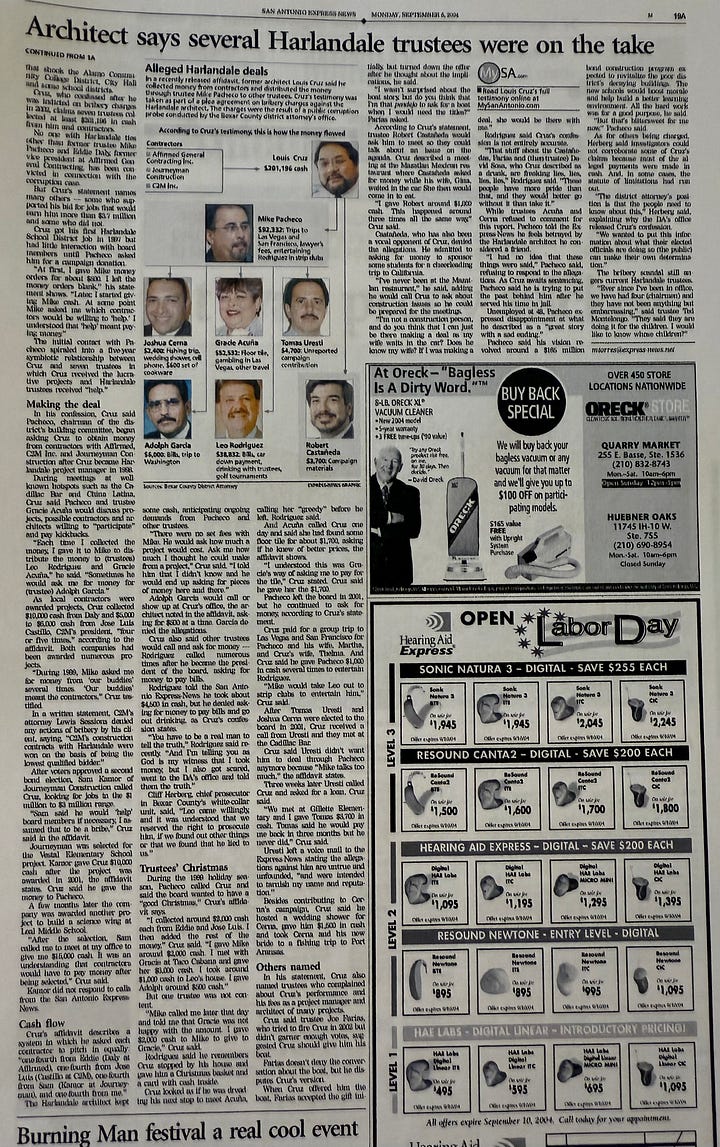

I walked back to my desk and began to read. The affidavit read like a crime novel. Page after page described Harlandale board members — former and present — shamelessly engaged in bribery and contractors willingly participating in a kickback system that gave them more contracts after trustees approved the work. It was a mafia-style organized crime way of doing business without the violence.

The final 10 pages of testimony were part of Cruz’s plea agreement with the prosecutor, which was made public after two former council members Raul Prado and Enrique Martin pleaded no contest and guilty, respectively, in the corruption probe.

Cruz was at the center of this kickback system, leading the charge and collecting money from contractors who paid to play. Cruz claimed that seven trustees collected at least $201,196 in cash from him and contractors to install expensive floor tiles in one board member’s house, pay for a wedding shower and pay for trips to Las Vegas and San Francisco and partying at strip clubs.

I had many questions for all these people, including a former trustee’s wife, who had become one of my sources.

After I read the affidavit, I called this woman and told her that I had some news but before I could share I needed to remind her of something.

“Do you remember that first conversation we had when I told you about my rules before you shared anything with me as a source?”

Yes, she said.

“Keep that in mind as you read the document,” I said.

My source knew well that I was talking about my rules of engagement, which we discussed when we first met for coffee.

I had three simple rules:

I’m not your friend — we are not friends.

If I find you’ve lied to me after providing me with any information, this arrangement is over.

If you or any of your close family members do something wrong and I need to write about it, please know that I will, because that’s my job.

I always clarify these rules when cementing source-reporter relationships.

I told my source that I would share the document and give her and husband 24 hours to review it and respond to the allegations that pertained to them. She understood my mission and supported it.

When I called her the next day, she said: “Do your job, Mc Nelly. Do your job.”

That’s what happens when you have clear rules with sources. When journalists are not clear, they are risking alienating people who feel betrayed after information they shared is attributed to them. I heard many stories of journalists doing this attributing, including some of my predecessors in numerous beats. I worked hard to navigate these relationships with integrity and show my approach would be different.

I interviewed her husband, who had vocally opposed Cruz and his behavior. I published his comments in the story.

Prosecutors charged none of the people implicated in the affidavit with crimes.

Nevertheless, I had a story to write and needed responses from people accused or implicated, because these were serious allegations.

I spent days calling, emailing and faxing questions. I drove to homes and knocked on doors, including one belonging to a female board member who had apparently demanded money for that floor tiles installation, which, it turned out, covered her whole house.

The story was published Sept. 6, 2004, on the Express-News metro front page, above the fold.

I persuaded the online folks to post the affidavit online, which was something they hadn’t ever done. The public had a right to review this document, read the same pages I read and draw their own conclusions about the people they voted into office as custodians of the tax dollars funding their children’s public schools.

A clear understanding

I can’t remember exactly how I found myself in the Lawton Police Department building’s basement, hanging with undercover detectives and a drug dog, but I remember the agreement we made before that door opened.

I knew who they were going to bust next for manufacturing and selling drugs and committing other crimes. I could see and read copies of the police’s search warrants related to the cases.

But to get the access, I agreed to be patient and hands-off. My reward would be an exclusive story after arrests took place.

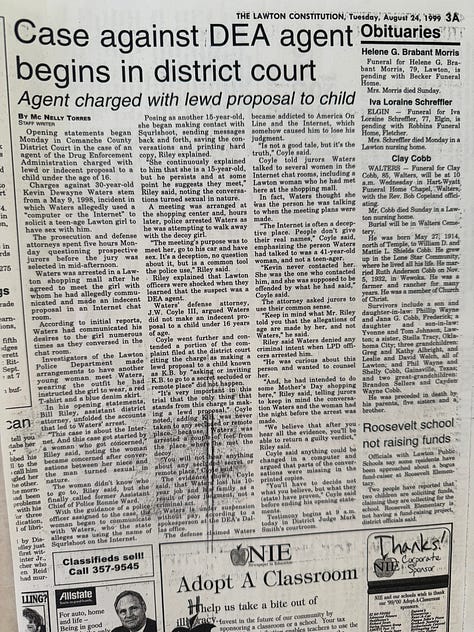

One Saturday afternoon, the head of the undercover unit called me with a peculiar request — to write a story about a man officers had arrested at the local shopping mall. The supervisor called that day even though he knew I did not work on weekends at The Lawton Constitution. But he called because he knew I’d take their calls anytime.

The supervisor seemed excited about the arrest. The detectives gave me the story because I’d earned their trust; they detested one of my newsroom peers whom detectives had caught following them around without their permission as they did their jobs.

I called my boss, the managing editor, and explained what we had. I said the arrest at the mall was the culmination of a monthslong sting operation.

The perp was an Oklahoma City man who tried to seduce a minor online. He had no idea that he was chatting with an undercover detective. He drove to Lawton to meet the presumptive young girl at a public place and had plans to take her to a motel.

Detectives had a decoy girl and law enforcement on site waiting for the perp to show.

But they were all for a big surprise when they discovered, after the arrest, that the perp was a Drug Enforcement Administration agent. Using a search warrant, law enforcement officials later found child pornography in his home computer.

This guy was married with children.

My boss gave me the OK to cover the story and promised to explain to my peer, who had followed the detectives, why he wouldn’t get to write it.

Although building sources is a powerful skill, it’s also a delicate dance. Integrity has always been at the center of everything I do as a journalist, and I know nothing in this job can be accomplished without candor and clarity. Or patience.

Only by laying out the rules could I have gotten the sourcing I needed for either story. Doing this required time, honesty and, sometimes, long waits. But this all pays off in the end.

Thanks for reading.

Follow Mc Nelly on Bluesky, Threads, LinkedIn, X, Substack Notes and be part of the community I’m building online. Drop me a note if you want to provide feedback, would like me to discuss a specific subject, collaborate or just to say hello at mcnellytorres@substack.com. Join our chat room here.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Tell me what you think

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.

Interesting story, McNelly.